Pages

Monday, October 30, 2023

The Pre-Columbian Pacific Coast

A Global Map Of The Last Glacial Maximum (And Dingos)

The earliest known dingo remains, found in Western Australia, date to 3,450 years ago. Based on a comparison of modern dingoes with these early remains, dingo morphology has not changed over thousands of years. This suggests that no artificial selection has been applied over this period and that the dingo represents an early form of dog. They have lived, bred, and undergone natural selection in the wild, isolated from other dogs until the arrival of European settlers, resulting in a unique breed.In 2020, an MDNA study of ancient dog remains from the Yellow River and Yangtze River basins of southern China showed that most of the ancient dogs fell within haplogroup A1b, as do the Australian dingoes and the pre-colonial dogs of the Pacific, but in low frequency in China today. The specimen from the Tianluoshan archaeological site, Zhejiang province dates to 7,000 YBP (years before present) and is basal to the entire haplogroup A1b lineage. The dogs belonging to this haplogroup were once widely distributed in southern China, then dispersed through Southeast Asia into New Guinea and Oceania, but were replaced in China by dogs of other lineages 2,000 YBP.The oldest reliable date for dog remains found in mainland Southeast Asia is from Vietnam at 4,000 YBP, and in Island Southeast Asia from Timor-Leste at 3,000 YBP. In New Guinea, the earliest dog remains date to 2,500–2,300 YBP from Caution Bay near Port Moresby, but no ancient New Guinea singing dog remains have been found. The earliest dingo remains in the Torres Straits date to 2,100 YBP.

The earliest dingo skeletal remains in Australia are estimated at 3,450 YBP from the Mandura Caves on the Nullarbor Plain, south-eastern Western Australia; 3,320 YBP from Woombah Midden near Woombah, New South Wales; and 3,170 YBP from Fromme's Landing on the Murray River near Mannum, South Australia.

Dingo bone fragments were found in a rock shelter located at Mount Burr, South Australia, in a layer that was originally dated 7,000-8,500 YBP. Excavations later indicated that the levels had been disturbed, and the dingo remains "probably moved to an earlier level."

The dating of these early Australian dingo fossils led to the widely held belief that dingoes first arrived in Australia 4,000 YBP and then took 500 years to disperse around the continent. However, the timing of these skeletal remains was based on the dating of the sediments in which they were discovered, and not the specimens themselves.In 2018, the oldest skeletal bones from the Madura Caves were directly carbon dated between 3,348 and 3,081 YBP, providing firm evidence of the earliest dingo and that dingoes arrived later than had previously been proposed. The next-most reliable timing is based on desiccated flesh dated 2,200 YBP from Thylacine Hole, 110 km west of Eucla on the Nullarbor Plain, southeastern Western Australia. When dingoes first arrived, they would have been taken up by indigenous Australians, who then provided a network for their swift transfer around the continent. Based on the recorded distribution time for dogs across Tasmania and cats across Australia once indigenous Australians had acquired them, the dispersal of dingoes from their point of landing until they occupied continental Australia is proposed to have taken only 70 years. The red fox is estimated to have dispersed across the continent in only 60–80 years.At the end of the last glacial maximum and the associated rise in sea levels, Tasmania became separated from the Australian mainland 12,000 YBP, and New Guinea 6,500–8,500 YBP by the inundation of the Sahul Shelf. Fossil remains in Australia date to around 3,500 YBP and no dingo remains have been uncovered in Tasmania, so the dingo is estimated to have arrived in Australia at a time between 3,500 and 12,000 YBP. To reach Australia through Island Southeast Asia even at the lowest sea level of the last glacial maximum, a journey of at least 50 kilometres (31 mi) over open sea between ancient Sunda and Sahul was necessary, so they must have accompanied humans on boats.

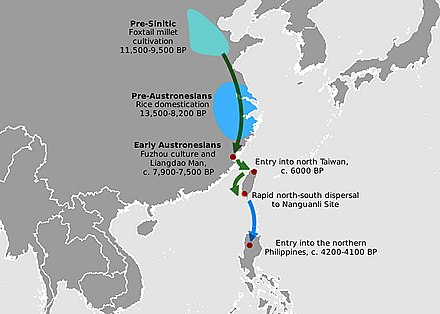

Some best estimates of Austronesian migration are as follows:

Wednesday, October 18, 2023

An Old Specimen Of Homo Erectus

With new paleomagnetic dating results and some description of recently excavated material, Mussi and coworkers show that levels D, E, and F are between 2.02 million and 1.95 million years old. Most interesting is that level D includes what is now the earliest Acheulean assemblage in the world, and level E has produced the partial jaw of a very young Homo erectus individual. The Garba IVE jaw is now one of two earliest H. erectus individuals known anywhere, in a virtual tie with the DNH 134 cranial vault from Drimolen, South Africa.

Tuesday, October 17, 2023

Modern Human Introgression Into Neanderthal DNA

Highlights

• Anatomically modern human-to-Neanderthal introgression occurred ∼250,000 years ago• ∼6% of the Altai Neanderthal genome was inherited from anatomically modern humans• Recent non-African admixture brought Neanderthal ancestry to some African groups• Modern human alleles were deleterious to NeanderthalsSummaryComparisons of Neanderthal genomes to anatomically modern human (AMH) genomes show a history of Neanderthal-to-AMH introgression stemming from interbreeding after the migration of AMHs from Africa to Eurasia.

All non-sub-Saharan African AMHs have genomic regions genetically similar to Neanderthals that descend from this introgression. Regions of the genome with Neanderthal similarities have also been identified in sub-Saharan African populations, but their origins have been unclear.

To better understand how these regions are distributed across sub-Saharan Africa, the source of their origin, and what their distribution within the genome tells us about early AMH and Neanderthal evolution, we analyzed a dataset of high-coverage, whole-genome sequences from 180 individuals from 12 diverse sub-Saharan African populations.

In sub-Saharan African populations with non-sub-Saharan African ancestry, as much as 1% of their genomes can be attributed to Neanderthal sequence introduced by recent migration, and subsequent admixture, of AMH populations originating from the Levant and North Africa.

However, most Neanderthal homologous regions in sub-Saharan African populations originate from migration of AMH populations from Africa to Eurasia ∼250 kya, and subsequent admixture with Neanderthals, resulting in ∼6% AMH ancestry in Neanderthals. These results indicate that there have been multiple migration events of AMHs out of Africa and that Neanderthal and AMH gene flow has been bi-directional.

Observing that genomic regions where AMHs show a depletion of Neanderthal introgression are also regions where Neanderthal genomes show a depletion of AMH introgression points to deleterious interactions between introgressed variants and background genomes in both groups—a hallmark of incipient speciation.

Daniel N. Harris, et al., "Diverse African genomes reveal selection on ancient modern human introgressions in Neanderthals" Current Biology (October 13, 2023). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.09.066

[T]hey compared the modern human genomes to a genome belonging to a Neanderthal who lived approximately 120,000 years ago. For this comparison, the team developed a novel statistical method that allowed them to determine the origins of the Neanderthal-like DNA in these modern sub-Saharan populations, whether they were regions that Neanderthals inherited from modern humans or regions that modern humans inherited from Neanderthals and then brought back to Africa.They found that all of the sub-Saharan populations contained Neanderthal-like DNA, indicating that this phenomenon is widespread. In most cases, this Neanderthal-like DNA originated from an ancient lineage of modern humans that passed their DNA on to Neanderthals when they migrated from Africa to Eurasia around 250,000 years ago. As a result of this modern human-Neanderthal interbreeding, approximately 6% of the Neanderthal genome was inherited from modern humans.In some specific sub-Saharan populations, the researchers also found evidence of Neanderthal ancestry that was introduced to these populations when humans bearing Neanderthal genes migrated back into Africa. Neanderthal ancestry in these sub-Saharan populations ranged from 0 to 1.5%, and the highest levels were observed in the Amhara from Ethiopia and Fulani from Cameroon.

Monday, October 9, 2023

Columbus Day Considered

Christopher Columbus was a pretty horrible person, so I have no problem ceasing to honor him with a national holiday. But he was also a uniquely important historical person whom everyone should know about, and the well attested date of his arrival, in 1492 CE, should also be something that every educated person knows.

Columbus was not the first person to make contact with the Americas after the arrival and dispersal of the predominant Founding populations of the indigenous people of South America, Mesoamerica, and most of North America around 14,000 years ago from Beringia where these populations had an extended sojourn in their migration to the Americas from Northeast Asia. They arrived with dogs, but no other domesticated animals.

There was at least one small progenitor wave of modern humans that reached at least as far as New Mexico before them about 21,000 or more years ago (as recent research has confirmed this year from earlier less definitive data), but unlike the Founding population of the Americas (itself derived from a genetically homogeneous population of less than a thousand Beringians), they left few traces and had little, if any, demographic impact on the Founding population that came after them, or had only the most minimal, if any, ecological impact on the Americas.

Columbus also arrived after the later arrival of two waves of migration from Siberia, one of which brought the ancestors of the Na-Dene people during what was the Bronze Age in Europe, and the second of which brought the ancestors of the Inuits during the European Middle Ages, both of whom were mostly limited to the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of North America, except for a Na-Dene migration to what is now the American Southwest around 1000 CE plus or minus (in part from pressure to move caused by the ancestors of the Inuit people). The Na-Dene ultimately heavily integrated themselves into the local population descended from the Founding population of the Americas. The Inuits admixed some, but much less, with the pre-existing population of the North American Arctic and largely replaced a population of "Paleo-Eskimos" who derived from the same wave of ancestors as the Na-Dene in the North American Arctic.

A few villages of Vikings settled for a generation or two in what is now Eastern Canada ca. 1000 CE before dying out or leaving (and leaving almost no genetic trace in people who continued to live in the Americas). And, the Polynesians (and perhaps others) probably made contact with the Pacific Coast of South America and Central America several times in the time frame (generously estimated) of ca. 3000 BCE to 1500 CE, again without a huge impact on the Americas or the rest of the world and with only slight amounts of admixture.

But the contact that Christopher Columbus made with the Americas persisted and profoundly changed both the Americas and the rest of the world. He returned to Europe and then came back with more Europeans who aimed to conquer the New World (including many covert Sephardic Jews seeking a more hospitable future than they had in Iberia).

Christopher Columbus's first contact led to a chain of events that resulted in the deaths of perhaps 90% of the indigenous population of the Americas (mostly due to the spread of European diseases like small pox and E. Coli, to which the people of the Americas had no immunity, at a time prior to the germ theory of disease, and only secondarily due to more concerted hostile actions taken by the European colonists towards the indigenous populations), led to the collapse of the Aztec and Inca civilizations at the hands of Spanish Conquistadors, brought syphilis to the Old World (especially Europe), brought horses to the Americas, led to the deforestation of much of North America, and brought crops native to the Americas including potatoes, maize, tomatoes, and hot chilis to the Old World (both Europe and Asia). Indirectly, this chain of events even led fairly directly to the Irish potato famine more than three centuries later.

Tuesday, October 3, 2023

Linguistic Terminology

One of the big issues in classification, mostly a terminology question, is where to draw the line between two ways of speaking and writing being dialects v. different languages, in part, because it often has political connotations.

"language" has two meanings: a generalized, abstract sense that comprises all human speech and writing, and the officially recognized speech and writing of a nation / country / gens — a politically united group of people.A topolect is the speech / writing of the people living in a certain place or area. It is geographically determined.A dialect is a distinctive form / style / pronunciation / accent shared by two or more people. To qualify as the speaker of a particular dialect, one must possess a pattern of speech, a lect, that is intelligible to others who speak the same dialect. As we say in Mandarin, it's a question of whether what you speak is jiǎng dé tōng 講得通 ("mutually intelligible") or jiǎng bùtōng 講不通 ("mutually unintelligible"). If what two people are speaking is jiǎng bùtōng 講不通 ("mutually unintelligible"), then they're not speaking the same dialect.Naturally, the dividing line between one dialect and another is not sharp. There is a blending, a gradation, a blurring between them. The same if true of languages on a larger scale. For example, I can understand close to a 100% of the speech of natives of Stark County, Ohio, but maybe only 75-80% of rapid speech from Vinton County in the south.An idiolect is spoken by only one person. . . ."Dialect" means so many radically different things, but also so many things that somewhat resemble each other, but are not really the same, that it is essentially useless for scientific purposes.

Antimatter Falls Down

This shouldn't be a surprise to anyone, but experiments have now confirmed, at the ALPHA Experiment at CERN, that anti-matter does indeed fall down, which is to say that its mass-energy has the same gravitational "charge" as all other mass-energy, rather than "falling up" and having a repulsive gravitational reaction to ordinary mass-energy. A link to the peer reviewed paper in Nature, and it abstract can be found here. The abstract states:

Einstein’s general theory of relativity (GR), from 1915, remains the most successful description of gravitation. From the 1919 solar eclipse to the observation of gravitational waves, the theory has passed many crucial experimental tests. However, the evolving concepts of dark matter and dark energy illustrate that there is much to be learned about the gravitating content of the universe. Singularities in the GR theory and the lack of a quantum theory of gravity suggest that our picture is incomplete. It is thus prudent to explore gravity in exotic physical systems. Antimatter was unknown to Einstein in 1915. Dirac’s theory appeared in 1928; the positron was observed in 1932. There has since been much speculation about gravity and antimatter. The theoretical consensus is that any laboratory mass must be attracted by the Earth, although some authors have considered the cosmological consequences if antimatter should be repelled by matter. In GR, the Weak Equivalence Principle (WEP) requires that all masses react identically to gravity, independent of their internal structure. Here we show that antihydrogen atoms, released from magnetic confinement in the ALPHA-g apparatus, behave in a way consistent with gravitational attraction to the Earth. Repulsive ‘antigravity’ is ruled out in this case. This experiment paves the way for precision studies of the magnitude of the gravitational acceleration between anti-atoms and the Earth to test the WEP.

The WEP has recently been tested for matter in Earth orbit with a precision of order 10-15. Antimatter has hitherto resisted direct, ballistic tests of the WEP due to the lack of a stable, electrically neutral, test particle. Electromagnetic forces on charged antiparticles make direct measurements in the Earth’s gravitational field extremely challenging . The gravitational force on a proton at the Earth’s surface is equivalent to that from an electric field of about 10-7 Vm-1. The situation with magnetic fields is even more dire: a cryogenic antiproton at 10 K would experience gravity-level forces in a magnetic field of order 10-10 T. Controlling stray fields to this level to unmask gravity is daunting. Experiments have, however, shown that confined, oscillating, charged antimatter particles behave as expected when considered as clocks in a gravitational field. The abilities to produce and confine antihydrogen now allow us to employ stable, neutral anti-atoms in dynamic experiments where gravity should play a role. Early considerations and a more recent proof-of-principle experiment in 2013 illustrated this potential. We describe here the initial results of a purpose-built experiment designed to observe the direction and the magnitude of the gravitational force on neutral antimatter.

This Year's Nobel Prize In Physics

The 2023 Nobel Prize in physics has been awarded to a team of scientists who created a ground-breaking technique using lasers to understand the extremely rapid movements of electrons, which were previously thought impossible to follow.Pierre Agostini, Ferenc Krausz and Anne L’Huillier “demonstrated a way to create extremely short pulses of light that can be used to measure the rapid processes in which electrons move or change energy,” the Nobel committee said when the prize was announced in Stockholm on Tuesday.