A new paper in Nature argues that genetic signals that have previously been interpreted as signs of archaic admixture in modern humans in Africa, actually reflect a process in which modern humans arose from two distinct gene pools in Africa of sub-species of ancestral modern humans that had a low, but non-zero level of interbreeding between them for hundreds of thousands of years.

There is a more educated layman oriented description of the paper's findings at the New York Times (paywalled), which is somewhat better than average for NYT science coverage.

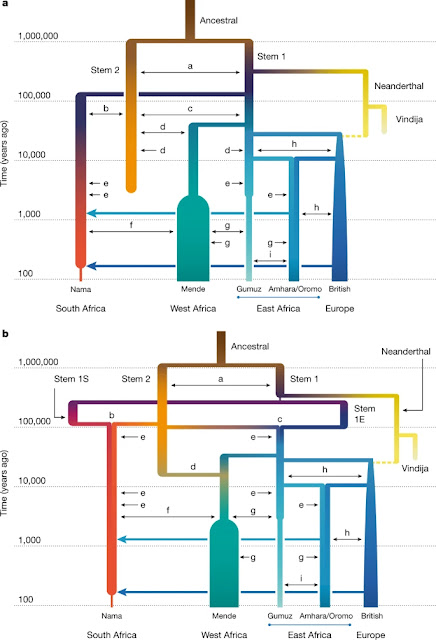

a,b, In the two best-fitting parameterizations of early population structure, continuous migration (a) and multiple mergers (b), models that include ongoing migration between stem populations outperform those in which stem populations are isolated. Most of the recent populations are also connected by continuous, reciprocal migration that is indicated by double-headed arrows. These migrations last for the duration of the coexistence of contemporaneous populations with constant migration rates over those intervals. The merger-with-stem-migration model (b, with LL = −101,600) outperformed the continuous-migration model (a, with LL = −115,300). Colours are used to distinguish overlapping branches. The letters a–i represent continuous migration between pairs of populations.

Despite broad agreement that Homo sapiens originated in Africa, considerable uncertainty surrounds specific models of divergence and migration across the continent. Progress is hampered by a shortage of fossil and genomic data, as well as variability in previous estimates of divergence times.

Here we seek to discriminate among such models by considering linkage disequilibrium and diversity-based statistics, optimized for rapid, complex demographic inference. We infer detailed demographic models for populations across Africa, including eastern and western representatives, and newly sequenced whole genomes from 44 Nama (Khoe-San) individuals from southern Africa.

We infer a reticulated African population history in which present-day population structure dates back to Marine Isotope Stage 5. The earliest population divergence among contemporary populations occurred 120,000 to 135,000 years ago and was preceded by links between two or more weakly differentiated ancestral Homo populations connected by gene flow over hundreds of thousands of years. Such weakly structured stem models explain patterns of polymorphism that had previously been attributed to contributions from archaic hominins in Africa.

In contrast to models with archaic introgression, we predict that fossil remains from coexisting ancestral populations should be genetically and morphologically similar, and that only an inferred 1–4% of genetic differentiation among contemporary human populations can be attributed to genetic drift between stem populations.

We show that model misspecification explains the variation in previous estimates of divergence times, and argue that studying a range of models is key to making robust inferences about deep history.

Aaron P. Ragsdale, et al., "A weakly structured stem for human origins in Africa" Nature (May 17, 2023) (open access) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06055-y

Part of the "Discussion" part of the paper lays out a narrative:

Our inferred models paint a consistent picture of the Middle to Late Pleistocene as a critical period of change, assuming that estimates from the recombination clock accurately relate to geological chronologies.

During the late Middle Pleistocene, the multiple-merger model indicates three major stem lineages in Africa, tentatively assigned to southern (stem 1S), eastern (stem 1E) and western/central Africa (stem 2). Geographical association was informed by the present population location with the greatest ancestry contribution from each stem. For example, stem 1S contributes 70% to the ancestral formation of the Khoe-San. The extent of the isolation 400 ka between stem 1S, stem 1E and stem 2 suggests that these stems were not proximate to each other.

Although the length of isolation among the stems is variable across fits, models with a period of divergence, isolation and then a merger event (that is, a reticulation) out-performed models with bifurcating divergence and continuous gene flow.A population reticulation involves multiple stems that contribute genetically to the formation of a group. One way in which this can happen is through the geographical expansion of one or both stems. For example, if, during MIS 5, either stem 1S from southern Africa moved northwards and thus encountered stem 2, or stem 2 moved from central–western Africa southwards into stem 1S, then we could observe disproportionate ancestry contributions from different stems in contemporary groups.

We observed two merger events. The first, between stem 1S and stem 2, resulted in the formation of an ancestral Khoe-San population around 120 ka. The second event, between stem 1E and stem 2 about 100 ka, resulted in the formation of the ancestors of eastern and western Africans, including the ancestors of people outside Africa.

Reticulated models do not have a unique and well-defined basal human population divergence. We suggest conceptualizing the events at 120 ka as the time of most recent shared ancestry among sampled populations. However, interpreting population divergence times in population genetics is always difficult, owing to the co-estimation of divergence time and subsequent migration; methods assuming clean and reticulated splits can infer different split dates. Therefore, in the literature, wide variation exists in estimates of divergence time.Shifts in wet and dry conditions across the African continent between 140 ka and 100 ka may have promoted these merger events between divergent stems. Precipitation does not neatly track interglacial cycles in Africa, and heterogeneity across regions may mean that the beginning of an arid period in eastern Africa is conversely the start of a wet period in southern Africa. The rapid rise in sea levels during the MIS 5e interglacial might have triggered migration inland away from the coasts, as has been suggested, for example, for the palaeo-Agulhas plain.

After these merger events, the stems subsequently fractured into subpopulations which persisted over the past 120 ka. These subpopulations can be linked to contemporary groups despite subsequent gene flow across the continent. For example, a genetic lineage sampled in the Gumuz has a probability of 0.7 of being inherited from the ancestral eastern subpopulation 55 ka, compared with a probability of 0.06 of being inherited from the southern subpopulation.We also find that stem 2 continued to contribute to western Africans during the Last Glacial Maximum (26 ka to 20 ka), indicating that this gene flow probably occurred in western and/or central Africa. Such an interpretation is reinforced by differential migration rates between regions; that is, the gene flow from stem 2 to western Africans is estimated to be five times that of the rate to eastern Africans during this period.

african multiregionalism rather then single origin

ReplyDeleteLocation of populations in the far past could be different than we see it in the present, so there is a place for other geographical interpretations of the story.

ReplyDeleteLet's try to look at this as follows:

1) Stem 1, as a closer to Neanderthals, was a Mediterranean one

2) Stem 2 was an Subsaharan one

3) Stem 1 expanded (or moved) to Subsaharan Africa through the East Africa in two waves subsequently admixing with Stem 2, the first wave (120 ky) created Stem 1S, and the second (100 ky) created Stem 1E

4) Before expanding to Euroasia, Stem 1E expanded to the West Africa continuously admixing with remaining part of Stem 2

isn't that multiregionalism

ReplyDelete@neo

ReplyDelete"isn't that multiregionalism"

Yes, a sort of it, yet limited to Africa (including North and North East of it) and unknown locations around the Middle East probably with the waves of Neanderthals and Stem 1 pushing to the South and North respectively.

I find 400 ky of isolation between Stems 1 and 2 (computed by the authors of the study) hardly imaginable within Subsaharan Africa.

Of course it is just a quick hypothesis but seems well fitted in this study's data and at the first glance I do not see strong contradiction in other data (like paleoclimatics or archeology)

In addition to being confined to Africa, contrary to historical multi-regional hypotheses, the multi-regional hypothesis envisioned more distinct stem groups.

ReplyDeleteThese populations are continuously part of the same species and are continuously interbreeding at very low levels. We are talking groups as only distinct as the modern Bantus v. Masai v. Khoe-San ethnicities within Africa.

Even advocates of bifurcating single origin theories have never suggested that at any one time there was a single Adam and a single Eve from whom everyone else is descended. There would have been at a minimum at least one community with some internal genetic diversity at any given time that experienced some pruning of lineages during times of widespread adversity like droughts and plagues, en route to modern humans today.

This paper expands on that to say that this common community that is a single species from which modern human arose had some mild regional structure that can be well summarized in two or three geographically separated communities within that larger common single species community with only low levels of reproductive interaction with each other at one time that were mildly adapted to their regions.

It is less of a multi-regional proposal and more of a plausible alternative way to understand genetic patterns in Africans that could otherwise be interpreted as archaic admixture with different species of modern humans entirely. So, in some ways it is actually a subtle rebuttal to multi-regionalism within Africa which would support that modern humans had roots in more than one ancestral species.

The known Neanderthal and Denisovan admixture in non-African modern humans without significant non-African modern human admixture, and with Denisovans in Asia and Oceania, especially on islands east of the Wallace line and in aboriginal Australians, is really the better fit to the multi-regional hypothesis.

ReplyDeleteWhat we understand now differs from the original multi-regional hypothesis more as a matter of degree than of kind.

The Neanderthal and Denisovan admixture percentages is much smaller than the multi-regionalists contemplated. Non-Africans have 0.5%-3% Neanderthal admixture. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neanderthal_genetics Denisovan admixture percentages outside a few relict populations in a few "hot spots" are under 0.5% in certain Asian and Oceanian and Australasian populations. But, there are a few "hot spot" relict populations where a few rare individuals may have up to 8% almost Denisovan admixture. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8596304/). Probably fewer than one in a million people have more than 4% archaic admixture combined, and the median combined percentage of archaic admixture for all non-Africans is probably under 2%.

But conceptually, archaic admixture is the real match to multi-regionalism and in the form of these two main waves of archaic admixture, this hypothesis is widely accepted.

"This paper expands on that to say that this common community that is a single species from which modern human arose had some mild regional structure that can be well summarized in two or three geographically separated communities within that larger common single species community with only low levels of reproductive interaction with each other at one time that were mildly adapted to their regions."

ReplyDeleteThe stem 1/stem 2 split predates the split between stem 1 and Neandersovans though. I think that finding is itself the most interesting.

Is stem 1 a subset of Neandersovans, or are Neaderthals just a subset of modern humans in a sense?

@Andrew

ReplyDelete"In addition to being confined to Africa, contrary to historical multi-regional hypotheses, the multi-regional hypothesis envisioned more distinct stem groups."

"unknown locations around the Middle East probably with the waves of Neanderthals and Stem 1 pushing to the South and North respectively."

I suspect that H sapiens are hybrid of many lineages including H erectus that occur in Africa

@neo

ReplyDeleteH. erectus almost surely couldn't produce fertile hybrid children with H. sapiens, and probably not even our close archaic ancestors.

@andrew - they seemed to have produced fertile children with Denisovans though at some point (perhaps early in Denisovans' history when they were less separated?)

ReplyDelete@neo

ReplyDeleteH. erectus almost surely couldn't produce fertile hybrid children with H. sapiens, and probably not even our close archaic ancestors.

@ andrew

Denisovans teen and jaw are neatly identical to H erectus

the large, robust molars which are more similar to those of Middle to Late Pleistocene archaic humans. The third molar is outside the range of any Homo species except H. habilis and H. rudolfensis, and is more like those of australopithecines. The second molar is larger than those of modern humans and Neanderthals, and is more similar to those of H. erectus and H. habilis.[20] Like Neanderthals, the mandible had a gap behind the molars, and the front teeth were flattened; but Denisovans lacked a high mandibular body, and the mandibular symphysis at the midline of the jaw was more receding.[12][18] The parietal is reminiscent of that of H. erectus.[39]

A facial reconstruction has been generated by comparing methylation at individual genetic loci associated with facial structure.[40] This analysis suggested that Denisovans, much like Neanderthals, had a long, broad, and projecting face; large nose; sloping forehead; protruding jaw; elongated and flattened skull; and wide chest and hips. The Denisovan tooth row was longer than that of Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans.[41]

OT Holocene Siberian population new paper by Choi Mentions Tarim Basin [DD: Aynu, Khotan] and Lake Baikal and Japan [DD: Ainu, Khotan = Ainu village]

ReplyDelete@DDeden Thanks for the head's up.

ReplyDelete

ReplyDeleteMy point was not about multiregional or single origin hypothesis but about geographical interpretation of the study.

What the study finds is a specific weak structure in the population created by specific events of short term or continuous mixing.

What we know about their geography is the current location of the three African subpopulations created by mixing of the Stems 1 and 2, the location of British people and the Vindija Neanderthal. But we do not have any direct information where the mixing occurred and from where the stems arrived to mix.

Yet we do have some hints:

- Stem 1 give rise to Neanderthals, so probably at the time of Neanderthals separation it was located in (or close to) Europe

- If so, we could interpret Stem 1 as the related to Home Heidelbergensis and Stem 2 as it's African analogues mixing continuously upto the time of Neanderthals separation and keeping apart each other for the subsequent 400 ky (and the two parts of stem 1 also kept apart of each other but starting their separation a bit later)

The question are:

- what was the location of the bottleneck in the Stem 1 shortly after the separation of Neanderthals

- what was the location (or changing locations) of 1E and 1S when their population increased

- how and when they appeared in Africa to mix with the Stem 2 by three events indicated in the study

Of course the geographical extent of Stem 1 could include Eastern or even Southern Africa earlier, yet we do not have any direct hints, rather the opposite.

@Maciej - I think it's interesting that all our Y chromosomes and mtDNA seem to come from Stem 1 too? Given a 700kya split date for the Denisovan and "original" Neanderthal Y chromosomes and mitochondrial DNA from modern humans, and a 1.2 mya split date between stems 1 and 2.

ReplyDeleteAnd in terms of that bottleneck in model B for Stem 1, I wonder how robust that finding is. I would think it would be evidence of a back-to-Africa event if it is real since it is not shared by Neanderthal's Stem 1 ancestors.

ReplyDelete@Ryan

ReplyDeleteYes, the career of our uniparental genes is strange. This dominance seems plausible in the case of incorporating small proportion of outer population (e.g. Moderns with Neanderthals admixture after OoA), but suspicious when taking the earlier incursion of this genes to Neanderthals and close to equal proportion of mixing with Stem 2 in the models of the study.

But at least theoretically, it could have worked in opposite direction - both Y chromosome and mtDNA (or one of them - in this case I would bet for Y) could come from stem 2 (and even Neandrethals could get their modern genes from Stem 2 somehow, although geographically this seems unlikely).

Stem's 1 bottleneck as 'Back to Africa' (or 'Out of Europe' at least?) could be an apt explanation. Thnx.

Press release at https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2023/05/230517121424.htm

ReplyDelete@Maciej - I believe the "original" Neandersovian uniparental markers we have still would be assigned to stem 1. Definitely interesting.

ReplyDeleteAnalysis from Razib at https://razib.substack.com/p/current-status-its-complicated

ReplyDeleteCommentary from John Hawks. https://johnhawks.net/weblog/ghostbusters-human-origins/

ReplyDelete