The deep history of humans in Africa and the complex divergences and migrations among ancient human genetic lineages remain poorly understood and are the subject of ongoing debate. We produced 73 high-quality whole genome sequences from 14 Central and Southern African populations with diverse, well-documented, languages, subsistence strategies, and socio-cultural practices, and jointly analyze this novel data with 104 African and non-African previously-released whole genomes. We find vast genome-wide diversity and individual pairwise differentiation within and among African populations at continental, regional, and even local geographical scales, often uncorrelated with linguistic affiliations and cultural practices.

We combine populations in 54 different ways and, for each population combination separately, we conduct extensive machine-learning Approximate Bayesian Computation inferences relying on genome-wide simulations of 48 competing evolutionary scenarios. We thus reconstruct jointly the tree-topologies and migration processes among ancient and recent lineages best explaining the diversity of extant genomic patterns. Our results show the necessity to explicitly consider the genomic diversity of African populations at a local scale, without merging population samples indiscriminately into larger a priori categories based on geography, subsistence-strategy, and/or linguistics criteria, in order to reconstruct the diverse evolutionary histories of our species.

We find that, for all different combinations of Central and Southern African populations, a tree-like evolution with long periods of drift between short periods of unidirectional gene-flow among pairs of ancient or recent lineages best explain observed genomic patterns compared to recurring gene-flow processes among lineages.

Moreover, we find that, for 25 combinations of populations, the lineage ancestral to extant Southern African Khoe-San populations diverged around 300,000 years ago from a lineage ancestral to Rainforest Hunter-Gatherers and neighboring agriculturalist populations.

We also find that short periods of ancient or recent asymmetrical gene-flow among lineages often coincided with epochs of major cultural and ecological changes previously identified by paleo-climatologists and archaeologists in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Gwenna Breton, et al., "Ancient tree-topologies and gene-flow processes among human lineages in Africa" bioRxiv (July 16, 2024).

Thus, human evolution and genetic structure in Africa is not well-described by more or less random genetic exchanges between neighboring populations. Instead, massive, short, unidirectional introgression (i.e. one people conquering another) is the norm.

African and Arabian Paleoclimate

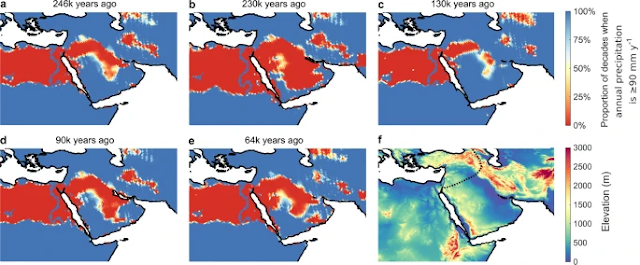

This paper leans heavily on Beyer, R.M. et al., "Climatic windows for human migration out of Africa in the past 300,000 years", 12(1) Nature Communications 4889 (2021) (open access), for its inferences based upon paleoclimate. Beyer (2021) concludes that:

there were a number of windows during the past 300k years when either northern or southern expansions out of Africa would have been climatically feasible. Prior to the last interglacial period, the Nile-Sinai-Land Bridge would have been crossable at several time intervals between 246k and 200k years ago. Following a reopening at 130k years ago, exits would have been intermittently possible until 96k years ago, and again later around 78k and 67k years ago.

After that, this route likely remained closed until the wet Holocene. Provided that maritime travel was in principle possible, climatic conditions would have made southern exits feasible for a substantial proportion of the last 300k years.

Before the last interglacial, there were three extended intervals of sufficient rainfall paired with relatively low sea level, from 275k to 242k years ago, from 230k to 221k years ago, and from 182k to 145k years ago. During most of the following window from 135k to 115k years ago, sea levels were particularly high, except at its beginning 135k years ago. This date is close to the proposed timing of an early northern exit; thus, if migration did occur, southern migrants might have encountered their northern counterparts on the Arabian Peninsula. Following a long period when the southern route was blocked, there was a sizeable window of sufficiently wet climate between 65k and 30k years ago.

Further connections existed just after the Last Glacial Maximum, and during the mid-Holocene, consistent with evidence of Eurasian backflow into Africa.

A threshold analogous to our estimate for precipitation exists for a Köppen aridity level around 1.7 based on the contemporary hunter-gatherer data, and the inferred periods of climatic connectivity between Africa and Eurasia are almost identical to those estimated for precipitation.

Our reconstructions suggest that there were several windows of suitable climate along either of the two possible dispersal routes that could have allowed the expansion of Homo sapiens out of Africa.

Some of these windows predate the earliest remains outside of Africa, but are entirely compatible with genetic dating of introgression from Homo sapiens into Neanderthal, sometime between 250k and 130k years ago, and recent dating of material from Israel to possibly 194k years ago and from Greece to 210k years ago.

Migrations into Eurasia were also likely feasible along both routes during the last interglacial period, when archaeological evidence points to a more sizeable exit. Two distinct scenarios for an exit around 65k years ago, the time that has been long suggested as the main moment of expansion out of the African continent based on archaeological and genetic evidence, are compatible with our estimates. This timing marks both the point shortly after which the northern route last was open before a period of 40k years of unsuitable climate, and the point at which the southern route first reopened for an extended period since the last interglacial period.

The latter scenario has been a subject of debate based on the empirical palaeoenvironmental record, with conclusions ranging from the Arabian Peninsula being continually too arid for human migration, to intermittent wet intervals, and extended pluvial periods during marine isotope stage 3 (57–29k years ago).

In any case, these inferences are not directly comparable with our results, both because several empirical proxies are not suitable for detecting rainfall of the small magnitude considered here (e.g. speleothems), and because, for each route, the specific path out of Africa that requires the least tolerance to low precipitation out of all possible paths varies over time, as does the geographic location of its driest segment; thus, our estimates would not be expected to necessarily display the same patterns over time as a localised empirical climate reconstruction. . . .

While archaeological and genetic data strongly suggest that Homo sapiens expanded its range towards Eurasia at least once prior to the large-scale colonisation wave beginning around 65k years ago, the reason for its initial failure to permanently settle outside Africa is less clear.

Migration beyond the Arabian Peninsula would have been predicated on the ability to cross the Taurus-Zagros Mountain range while competing with Neanderthals in the north, which has previously been argued to have limited human expansions during the last interglacial period, and possibly other hominins, such as Denisovans (whose geographic range is unknown but likely covered a large portion of East Asia), in the east.

In addition, our reconstructions suggest that climatically favourable intervals along both routes were frequently interrupted by periods of rainfall insufficient to support humans, which would have effectively isolated any of the earlier colonists that might have made it out of Africa. With a lack of demographic influx from further migration out of Africa, remnant populations on the Arabian Peninsula would have been susceptible to stochastic local extinctions driven by climatic fluctuations.

This constraint would have been less important along the southern route during the unprecedentedly long period of largely favourable climate between 65k and 30k years ago, provided that maritime travel across a then 4 km wide strait of the Bab e-Mandeb made migration along this route possible. This long window would have provided ideal preconditions for a successful large-scale dispersal, allowing for a regular demographic influx from Africa that would have stabilised populations on the Arabian Peninsula, thus facilitating further expansion of Homo sapiens into Eurasia.

These dynamics would have complemented technological, economic, social, and cognitive changes in human societies, which, possibly combined with the decline of Neanderthal, very probably accounted for the success of the late exit in the subsequent colonisation of Eurasia by Homo sapiens.

Khoisan Origins

The Khoisan hunter gatherers of Africa have had distinct northern and southern subpopulations since roughly the time of genetic Out of Africa (ca. 50,000-80,000 years ago). This is a branch depth as deep as the divisions between Australian Aboriginal people and Swedish people in populations that live on opposite sides of the Kalahari desert in Southern Africa. The authors hypothesize that:

the global climatic shifts inducing massive ecological changes that have occurred in Africa at that time (e.g. (Beyer et al., 2021)), sometimes proposed to have triggered ancient Homo sapiens movements Out-of-Africa, may also have triggered, independently, the genetic isolation among ancestral Khoe-San populations. Nevertheless, where the ancestors of extant Khoe-San populations lived at that time remains unknown and is nevertheless crucial to further elaborate possible scenarios for the causes of the genetic divergence here inferred.

The common Khoisan ancestor population became distinct from other modern humans around 300,000 years ago, around the time that the modern human species emerged.

The Origins Of The Pygmies And Their Neighbors

Among Rainforest Hunter Gathers (RHG) in the Congo jungle, a.k.a. the Pygmies, there are genetically distinct populations in the West and in the East that date roughly to the Last Glacial Maximum (17,000 to 27,000 years ago). The authors explain that:

Rainforest Hunter-Gatherer populations across the Congo Basin diverged roughly between 17,000 and 27,000 years ago, relatively consistently across pairs of sampled populations used for inferences; estimates highly consistent with previous studies, despite major differences in gene-flow specifications across RHG groups between studies. Interestingly, this divergence time is relatively synchronic with absolute estimates for the Last-Glacial Maximum in Sub-Saharan Africa. The fragmentation of the rainforest massif during this period in the Congo Basin may have induced isolation between Eastern and Western RHG extant populations, as plausibly previously proposed. However, similarly as above for the Northern and Southern Khoe-San populations divergence, where the ancestors of extant Eastern and Western Rainforest Hunter-Gatherers lived remains unknown, which prevents us from formally testing this hypothesis.

This is around the time of the division between the founding population of the Americas and the populations of East Asia and Northeast Asia from which they originated. It is also a time frame during which Europe was depopulated except for relict populations in Iberia, the Italian Peninsula, and the Caucuses.

The population ancestral to Rain Forest Hunter gathers and their agricultural neighbors branched between the neighboring population and the Rain Forest Hunter gatherer population, about 165,000 years ago.

Key Short Duration Admixture Events In Africa

But, there were admixture events after that date. The authors explain that:

we found strong indications for almost synchronic events of introgressions having occurred during the Last Interglacial Maximum in Africa (Mazet et al., 2016), between ~90,000 and ~135,000 years ago (when considering 20 or 30 years per generation). They involved gene-flow between lineages ancestral to Khoe-San populations and ancestors of Rainforest Hunter-Gatherer neighbors on the one hand and, on the other hand, between lineages ancestral to Khoe-San populations and the lineage ancestral to all Rainforest Hunter-Gatherers.

An increase in material-based culture diversification and innovation, possibly linked to climatic and environmental changes locally, has previously been observed during this period of the Middle Stone Age in diverse regions of continental Africa; prompting a long-standing debate as to its causes if human populations were subdivided and isolated biologically and culturally at the time[.] . . .

the instantaneous gene-flow event between the ancestral Rainforest Hunter-Gatherers lineage and that of their extant neighbors seemingly occurred synchronically to the genetic Out-of-Africa ((Beyer et al., 2021); see above). This would imply that possible climatic and ecological shifts at that time may not have only induced population divergences and displacement, but may also have triggered population gene-flow.

There was also a gene flow event between populations in Rain Forest Hunter Gather neighbors population, and the northern and southern Khoisan populations:

around 30,000 years ago, we found two loosely synchronic gene-flow events between ancestors to extant Central African Rainforest Hunter-Gatherer neighbors’ lineages and, separately, Northern and Southern Khoe-San lineages. This corresponds to the end of the Interglacial Maximum and a period of major cultural changes and innovations during the complex transition from Middle Stone Age to Late Stone Age in Central and Southern Africa. Nevertheless, connecting the two lines of genetic and archaeological evidence to conclude for increased population movements at the time and their possible causes should be considered with caution. Indeed, in addition to genetic-dating credibility-intervals being inherently much larger than archaeological dating, this period remains highly debated in paleoanthropology mainly due to the scarcity and complexity of the material-based culture records, and that of climatic and ecological changes locally, across vast regions going from the Congo Basin to the Cape of Good Hope.

And, there were also multiple gene flow events in the early Holocene era (roughly corresponding to the Neolithic era in Europe and into the European Copper/early Bronze Age):

we found strong signals for multiple instantaneous gene-flow events having occurred between almost all five recent Central and Southern African lineages between 6000 and 12,000 years ago, during the onset of the Holocene in that region, shortly before or during the beginning of the last Post Glacial Maximum climatic crisis in Western Central Africa, the emergence and spread of agricultural techniques, and the demic expansion of now-Bantu speaking populations from West Central Africa into the rest of Central and Southern Africa. These results are consistent with previous investigations that demonstrated the determining influence of Rainforest Hunter-Gatherer neighboring populations’ migrations through the Congo Basin in shaping complex socio-culturally determined admixture patterns, including admixture-related natural selection processes.As our estimates for introgression events are in the upper bound of previous estimates for the onset of the so called “Bantu expansion” throughout Central and Southern Africa, we may hypothesize here that major climatic and ecological changes that have occurred at that time may have triggered increased population mobility and gene-flow events between previously isolated populations, rather than consider that the Bantu-expansions themselves were the cause for all the gene-flow events here identified.Finally, we did not find signals of more recent introgression events from Bantu-speaking agriculturalists populations into Northern or Southern Khoe-San populations, in particular among the !Xun, albeit such events have been identified in several previous studies (see (Schlebusch and Jakobsson, 2018)). This is likely due to the fact that we considered only a limited number of individual samples from each population, and therefore may lack power to detect these very recent events with our data and approach.

Was There Archaic Admixture In Africa?

The new paper finds that it is possible to fit their data to a narrative without admixture with a ghost population of archaic hominins in Africa, as some studies have suggested, although that possibility is not ruled out either, and the authors of this study acknowledge that they are using fewer kinds of data to build their historical narratives than studies that found evidence of admixture with ghost archaic hominin populations in Africa.

Ragsdale and colleagues included in their models possible very ancient genetic structures, long before Homo sapiens emergence, a feature that is unspecified in our scenarios which considered simply a single ancestral population in which all extant lineages ultimately coalesce. Nevertheless, note that substructure and reticulation within the ancestral population is not per se incompatible with our scenarios. In fact, it may be compatible with our posterior estimates of a large effective population ancestral to all extant populations here investigated, the largest among all inferred ancient and recent Central and Southern African effective population sizes. . . . .

We did not explore possible contributions from unsampled lineages, whether from non-Homo sapiens or from ancient “ghost” human populations, and therefore cannot formally evaluate the likeliness of the occurrence of such events to explain observed data. In all cases, our results demonstrate that explicitly considering ancient admixture from unsampled populations is not a necessity to explain satisfactorily large parts of the observed genomic diversity of extant Central and Southern African populations, consistently with a previous study (Ragsdale et al., 2023), and conversely to others (Lipson et al., 2022; Fan et al., 2023; Pfennig et al., 2023); at least when considering jointly the 337 relatively classical population genetics summary-statistics used here for demographic inferences. As discussed above, our results formally comparing competing-scenarios rather than comparing posterior likelihoods of highly complex yet vastly differing models, provide a clear and reasonable starting point for future complexification of scenarios comprising possible contributions from ancient or ghost unsampled populations, which will unquestionably benefit from the explicit use of additional novel summary statistics ((Ragsdale and Gravel, 2019; Fan et al., 2023; Ragsdale et al., 2023); see also above).

In any case, the complexification of scenario-specifications to account for possible past “archaic” or “ancient” introgressions will not fundamentally solve the issue of the current lack of reliable ancient genomic data older than a few hundreds or thousands of years from Sub-Saharan Africa. Indeed, analogously to archaic admixture signals that were unambiguously identified outside Africa only when ancient DNA data were made available for Neanderthals and Denisovans (e.g. (Meyer et al., 2012; Prüfer et al., 2014)), we imperatively need to overcome this lack of empirical ancient DNA data in Africa to formally test whether, or not, ancient human or non-human now extinct lineages have contributed to shaping extant African diversity.

Side Observations Re Non-African Admixture

The study also made some side observations. For example, in its ancestry analysis at K=2 it effectively shows that amount of non-sub-Saharan African admixture present in various African populations.

Unsurprisingly, this admixture is lowest in hunter-gather populations, modestly higher among non-hunter-gatherer Central and Southern Africans, higher still among the most northern East Africans, high among "Coloured" South Africans who have substantial non-African admixture, and predominantly non-African among North Africans.

Within non-Africans, Papuans pop out as a distinct population at K=5, and indigenous peoples of the Americas pop out as distinct at K=6.

Genetic Variation and Diversity

The paper also confirms conventional wisdom that African populations have more genetic diversity than non-Africans, even within sub-populations (and not merely because it is a large continent with many subpopulation that differ from each other). The amount of genetic variation in any subpopulation is strongly correlated with the amount of non-African admixture in a subpopulation (which less genetic variation associated with more non-African ancestry).

Weaknesses In The Paper

The most notable gap in the sample is a lack of DNA from Mozambique, whose people in Southeast Africa are known to be genetically quite distinct from other Africans, which local Bantu languages have click phonemes, presumably from a pre-Bantu substrate language.

The paper would also benefit from straying beyond its focus on the most basal populations of Africa to explore, at an at least superficial level, how this Central and Southern African population history fits into the larger global population of Homo sapiens.

No comments:

Post a Comment