Maya occupation at Cuello (modern-day Belize) has been carbon dated to around 2600 BC. Settlements were established around 1800 BC in the Soconusco region of the Pacific coast, and the Maya were already cultivating the staple crops of maize, beans, squash, and chili pepper.

Eventually, these crops would spread to include essentially all of the Mississippi River basin in the Mississippian culture, and beyond to replace a less successful package of food production crops in what is now the American Southeast.

This chronology also helps to harmonize the amount of time between the development of a full fledged Neolithic culture in the Americas and the subsequent development of metalworking in the Americas.

It also disfavors the hypothesis that technological development in food production and otherwise in the Americas was triggered by the arrival of the ancestors of the Na-Dene people in North America via Alaska fairly close in time to the development of the Mayan civilization.

Between the ethnogenesis of the fused Maya population and the present, the region has experienced an introgression of about 25% of the gene pool from the Mesoamerican highlands. Only about 23% of the modern Mayan gene pool is traceable to population present in the lowlands of Mesoamerica before this demic diffusion of agriculture occurred, while 52% of the modern Mayan gene pool is attributable to this migration of South American corn farmers (exclusive of 7% European and 1% African ancestry in modern Maya populations from the post-Columbian era).

Top: dates of individuals with genetic data (individual 95.4% confidence intervals and total summed probability density; MHCP.19.12.17 [low-coverage] omitted for scale). *Date based on association with familial relative.

Bottom: earliest radiocarbon dates associated with microbotanical evidence for maize, manioc, and chili peppers in the Maya region and adjacent areas at Lake Puerto Arturo, Guatemala (GT); Cob Swamp, Belize (BZ); Rio Hondo Delta; Caye Coco, BZ; and Lake Yojoa, Honduras (HN), together with summed probability distribution of the earliest maize cobs (n = 11) in southeastern Mesoamerica from El Gigante rock-shelter, HN. Also shown in yellow is the known transition to staple maize agriculture based on dietary stable isotope dietary data from MHCP and ST.

This reflux model of corn domestication is new. Most previous scholarship had implicitly assumed that corn domestication was refined in situ in the Mesoamerican region where its wild type ancestor is found and was at something of a loss to explain why it took 3,400 years for it to really take hold as a major food source.

The introduction to the paper explains that:

Maize domestication began in southwest Mexico ~9000 years ago and genetic and microbotanical data indicate early dispersal southward and into South America prior to 7500 cal. BP as a partial domesticate before the complete suite of characteristics defining it as a staple grain had fully developed.

Secondary improvement of maize occurred in South America, where selection led to increased cob and seed size beyond the range of wild teosinte progenitor species. Maize cultivation was widespread in northwestern Colombia and Bolivia by 7000 cal. BP.

The earliest evidence for maize as a dietary staple comes from Paredones on the north coast of Peru, where dietary isotopes from human teeth suggest maize shifted from a weaning food to staple consumption between 6000–5000 cal. BP consistent with directly dated maize cobs. Maize cultivation was well-established in some parts of southern Central America (e.g., Panama) by ~6200 cal. BP.Starch grains and phytoliths recovered from stone tools from sites in the southeastern Yucatan near MHCP and ST indicate that maize (Zea mays), manioc (Manihot sp.) and chili peppers (Capsicum sp.) were being processed during the Middle Holocene, possibly as early as 6500 cal. BP.

Paleoecological data (pollen, phytoliths, and charcoal) from lake and wetland cores point to increases in burning and land clearance associated with early maize cultivation after ~5600 cal. BP.

Maize was grown at low levels after initial introduction, and there is greater evidence for forest clearing and maize-based horticulture after ~4700 cal. BP. Increases in forest clearing and maize consumption coincide with the appearance of more productive varieties of maize regionally, which have been argued based on genetic and morphological data to to be reintroduced to Central America from South America.The increases in burning, forest disturbance, and maize cultivation in southeastern Yucatan evident after ~5600 cal. BP, as well as the subsequent shift to more intensified forms of maize horticulture and consumption after ~4700 cal. BP, can be plausibly linked to: 1) the adoption of maize and other domesticates by local forager-horticulturalists, 2) the intrusion of more horticulturally-oriented populations carrying new varieties of maize, or 3) a combination of the two.

Dispersals of people with domesticated plants and animals are well documented with combined archeological and genome-wide ancient DNA studies in the Near East; Africa; Europe; and Central, South, and Southeast Asia. The spread of populations practicing agriculture into the Caribbean islands from South America starting ~2500 years ago is also well documented archeologically and genetically.

However, in the American mainland, the generally accepted null hypothesis is that the spread of horticultural and later farming systems typically resulted from diffusion of crops and technologies across cultural regions rather than movement of people. Here, we examined the mode of horticultural dispersal into the southeastern Yucatan with genome-wide data for a transect of individuals from MHCP and ST with stable isotope dietary data and direct AMS 14C dates between 9600 and 3700 cal. BP.

The paper continues in its discussion section to state that:

[O]ur results support a scenario in which Chibchan-related horticulturalists moved northward into the southeastern Yucatan carrying improved varieties of maize, and possibly also manioc and chili peppers, and mixed with local populations to create new horticultural traditions that ultimately led to more intensive forms of maize agriculture much later in time (after 4700 cal. BP).

The oldest individuals from Belize dated between 9600 and 7300 years old cluster together, close to the ancient individuals from South America.

More recent individuals from Belize dated between 5600 and 3700 years old are shifted to the left in the direction of present-day populations speaking a Chibchane language from northern Colombia and Venezuela. Current populations speaking a Maya language are located close to the ancient individuals from Belize dated between 5600 and 3700 years ago, but slightly shifted towards the Mexican populations of the highlands. . . . [T]he population represented by the ancient individuals from Belize dated between 5600 and 3700 years ago can be modeled as resulting from a genetic mixture between a population represented by the ancient individuals from Belize dated between 9600 and 7300 years ago (31%) and a population ancestor of the Chibchan populations (69%). These results suggest Chibchane gene flow in the ancient population of Belize. They are also supported by the discontinuity of mitochondrial haplogroups between 7300 and 5600 years ago. . . .This flow of genes from the south is linked to the arrival of a Chibchane population from the south of the Maya region which probably contributed to the development of the cultivation of maize, and perhaps also other domesticated plants.On the other hand the current Maya population can be modeled as resulting from a genetic mixture between the ancient population of Belize dated between 5600 and 3700 years ago (75%) and a population related to the ancestors of the Mexican populations of the highlands (25%) such as the Mixes , Zapotecs and Mixtecs.

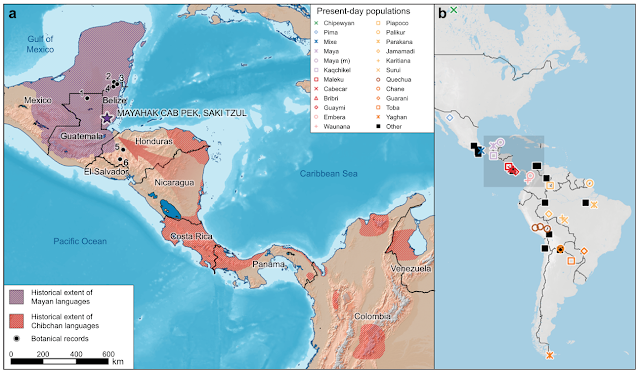

The distribution and history of languages in Central America provides an independent line of evidence for our proposed historical interpretation.

Chibchan is a family of 16 extant (7–8 extinct) languages spoken from northern Venezuela and Colombia to eastern Honduras. The highest linguistic diversity of the Chibchan family occurs today in Costa Rica and Panama near the Isthmian land bridge to South America, and this is hypothesized to be the original homeland from which the languages diversified, starting roughly 5500 years ago.

We undertook a preliminary analysis of 25 phonologically and semantically comparable basic vocabulary items to study the linguistic evidence for interaction between early Chibchan and Mayan languages, of which a subset of 9 display minimally recurring and interlocking sound correspondences.

We also focused on possible borrowings: crucially, one of the terms for maize, #ʔayma, diffused among several languages of northern Central America (Misumalpan, Lenkan, Xinkan), as well as the branch of Mayan that broke off earlier than any other (Huastecan). This term is much more phonologically diverse and much more widely distributed (both across linguistic branches and geographically) in Chibchan than in any other non-Chibchan language of Central America or Mexico, and it is morphologically analyzable in several Chibchan languages, including a final suffix.

Together, these traits support a Chibchan origin of this etymon, which could correspond to a variety of maize introduced from the south. Formal linguistic analysis over a much larger dataset will be necessary to understand the early sharing patterns (of both inheritance and diffusion) between these two language groups, which may provide further clues about the movements of material culture and people we discuss here.

The genetic prehistory of human populations in Central America is largely unexplored leaving an important gap in our knowledge of the global expansion of humans. We report genome-wide ancient DNA data for a transect of twenty individuals from two Belize rock-shelters dating between 9,600-3,700 calibrated radiocarbon years before present (cal. BP).

The oldest individuals (9,600-7,300 cal. BP) descend from an Early Holocene Native American lineage with only distant relatedness to present-day Mesoamericans, including Mayan-speaking populations.

After ~5,600 cal. BP a previously unknown human dispersal from the south made a major demographic impact on the region, contributing more than 50% of the ancestry of all later individuals. This new ancestry derived from a source related to present-day Chibchan speakers living from Costa Rica to Colombia. Its arrival corresponds to the first clear evidence for forest clearing and maize horticulture in what later became the Maya region.

3 comments:

Hi Andrew, One blog that you might consider linking to from here is https://acoup.blog/. It's part of my weekly rotation, deep and meaty, and not to controversial. From WPP you might consider directing folks to Freddie deBoer's blog https://freddiedeboer.substack.com/. Cheers,

Guy

Thank you for the recommendations. I'm always on the lookout for good new blogs to read.

If I read correctly, the nub of the matter comes here: "However, in the American mainland, the generally accepted null hypothesis is that the spread of horticultural and later farming systems typically resulted from diffusion of crops and technologies across cultural regions rather than movement of people."

So the default assumption in the field is the Marxist-inspired anti-imperialist position that in pre-history, all cultural diffusion was by ideas transferred village to village, and not by invasion and population replacement. Pots, not people. Because if you're fighting against colonialism in the 20th century, you certainly don't want it to look like migration and conquest are in any sense historically natural, do you?

Of course, now that we have ancient DNA, the entire edifice of late 20th century anthropology/archaeology has gone down the toilet. People did migrate and bring their cultures with them. And pots, not people has become a caution, and no longer a consensus-inforced ideology.

The fact that diffusion without migration was ever considered a default position just shows that the field was corrupted by ideology. If the presence of ceramic styles - or maize horticulture - doesn't prove that migrating peoples carried them, it doesn't prove that such cultures spread neighbor by neighbor, village by village over hundreds of miles either.

The anti-migrationist orthodox consensus never imagined that ancient DNA would come along and knock down the life's work of the leaders of their field.

Post a Comment