About half of this blog's posts are devoted to developments in human evolution and our understanding of human pre-history and ancient history. Midway into 2024, what are the hot issues that are outstanding in these fields?

Archaic Hominins

What ecological pressures drove early hominin evolution from a common ancestor of, or sister clade to chimpanzees and bonobos?

When did early hominins become bipedal and why?

Why did modern humans lose most of their body hair?

Precisely which archaic hominin species were ancestral to modern humans and which were "dead ends"?

Which archaic hominin species could produce hybrid offspring with each other? We know that there was modern human-Neanderthal admixture, modern human-Denisovan admixture, Neanderthal-Denisovan admixture, and Denisovan-super archaic admixture. Did Homo floresiensis have hybrid offspring with modern humans? Was there any archaic admixture with modern humans in Africa, and if so, in whom is a legacy of this (if any) found today?

What species is the source of super-archaic admixture in Denisovans? Did Denisovans admix with Homo erectus or with Homo floresiensis?

What did Denisovans look like? What were their lives like? How smart were they?

What was the population structure within Denisovans like and what waves of Denisovan populations existed and replaced each other?

What archaic hominin species were present in Africa and when?

What archaic hominin species were present outside of Africa and when and how did they get there?

When and why did various archaic hominin species go extinct (especially outside of Africa)? Why did the Neanderthals go extinct? Are there any relict archaic hominin populations in the world? If not, when did the last relict population of archaic hominins go extinct? Why did the Neanderthals go extinct? Why did the Denisovans go extinct? Why did Homo floresiensis go extinct? Are our legends of human-like fairies, elves, dwarves, Yeti, trolls, etc. oral history recollections of our contacts with archaic hominins?

Precisely when, where, why, and how (within Africa) did modern humans evolve from archaic hominins?

Which archaic hominin species interacted directly with modern humans?

To what species should the Julurens archaic hominin remains in China be assigned?

Do the Homo erectus-homo sapien mosaic feature skulls in China represent hybrid species individuals, or separate species of the genus Homo?

Prehistory and Ancient History

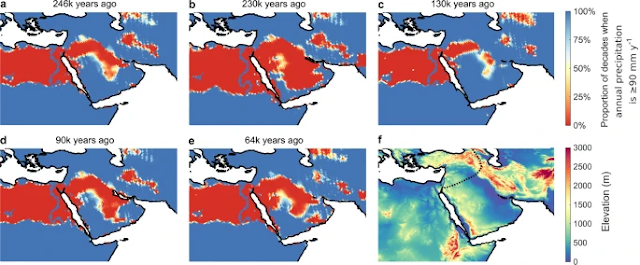

Why is the archaeological evidence for modern humans in the range from Arabia to India so much earlier than the genetic indications of the main Out of Africa expansion?

What connection was there between the expansion of modern humans from India to Southern Asia, the extinction of Homo erectus, and the Toba eruption?

What were the main waves of modern human expansion into Asia? How much did later waves replace earlier waves?

How much substructure was there in the founding population of the Americas settlement of the Americas?

There is evidence of a modern human presence in the Americas many thousands of years before the main founding population wave(s). Why didn't this early modern human presence thrive and leave more of a mark? Was this a single continuous event, or were there multiple false start migrations that successively failed? Where there any modern humans left in the Americas when the first wave of the founding population of the Americas arrived?

What narrative explains the apparent Paleo-Asian ancestry in select indigenous tribes in South America?

What post-founding era, pre-Columbian contracts were there between the Americas and modern humans from the "Old World"?

What was the biggest level of societal structure in the hunter-gatherer era of humanity? What was life like in those tribes?

Was Göbekli Tepe really pre-Neolithic? Was it connected with a Neolithic era false start? What made it possible? Do its inscriptions document a Younger Dryas causing extra-terrestrial impact?

What did the process of assembling a full Neolithic package of domesticates in the Fertile Crescent from multiple places of domestication in that region look like? What were relations like between Caucasian hunter-gatherers and their first farmer descendants, and Levantine hunter-gatherers and their first farmer descendants, as the two populations were very genetically distinct but cooperated to assemble the full Fertile Crescent Neolithic package?

What did the pre-Indo-European linguistic landscape look like? Did the languages of the European hunter-gatherers leave any trace (e.g. in linguistic substrates or loan words)? Were the languages of the pre-Indo-European farmers of Europe, presumably including Basque, all derived from a single language family of the first farmers of Western Anatolia?

Was there a macro-family of ergative languages in Mesopotamia, Anatolia, the Caucuses, and West Asia? Do the languages of the Caucuses have a common origin, and if so, are they related to this possibly macro-family of ergative languages? Was the Harappan language part of one or both of these language families? Did this language family extend to North Africa?

Was there a cultural and linguistic and religious replacement by conquest in Anatolian sometime between the late Neolithic era and the early Bronze Age giving rise to the Hattic people with a demic component?

When did the various pre-Indo-European languages of Europe and West Asia (except Basque) go extinct?

Where and how did the Indo-European languages originate?

What is the timeline and geography of Indo-European languages? What is the correct phylogeny of the Indo-European languages? What is the correct origin story for each Indo-European language, particularly, ambiguous and possibly complex cases like Armenian?

Did the Corded Ware people, the Yamnaya people, and the Bell Beaker people speak the same Indo-European language? Why did the Corded Ware people and the Yamnaya people have such distinct Y-DNA ancestry despite having similar autosomal ancestry, familial patterns, and a shared presumed language family?

What Indo-European languages were spoken by the Bell Beaker people and their descendants before Celtic and Germanic languages in the narrow sense emerged? How similar were they culturally and linguistically to the historically attested early Celtic and Germanic peoples? What was the nature of the interactions and feelings of the Bell Beaker people and Corded Ware people towards each other?

What is the story behind the dramatic surge in lactose tolerance genes shortly after Indo-Europeans arrived in Western Europe?

When did the Indo-European Anatolian languages arise and why were they so distinct from other Indo-European languages?

Was the Minoan culture an offshoot of the pre-Hittite Anatolian Hattic culture or a larger linguistic and cultural family?

What was the Harappan culture like and what languages, if any, was its language related to?

What was the exact chronology of Indo-European migration to what is now Iran and to South Asia? What were the main outlines of its waves of expansion within India?

How did Hinduism emerge from Harappan and Indo-Iranian religious practices and beliefs? What caused the divergence between it and the ancient Iranian religion? When did particular practices and beliefs, like vegetarianism and the sacred cow emerge?

What was the social structure in India like between the Indo-Aryan arrival and the establishment of strict jati endogamy much later?

Is the Dravidian language related to any other existing or extinct language? When did it arise? When did its branches arise? How did the Brahui come to speak a version of it? Why does the language family seem less diverse and younger than plausible theories about its time of origin? Did it contract in the face of Indo-Aryan expansion and then reclaim much of South Asia? Does the Dravidian language family and the culture of the Dravidian people have any connections to Niger-Congo languages and the cultures of the people in the Sahel of Africa who domesticated many key crops of the South Indian Neolithic Revolution? Does Y-DNA T, which has a peculiar geographic distribution in India have any connection to the origin story of the Dravidian languages?

What is the origin story of the Chadic people? What about the Fulani people and their languages?

How are the Afro-Asiatic languages related to each other and what are there respective origin stories in time and space?

When did the Berber languages emerge? What preceded them?

What is the origin story of the emergence and spread of the Nilo-Saharan languages?

When did the languages spoken by the Pygmies in Africa die? Are there any traces, such as in linguistic substates or loan words of Bantu languages, of those lost languages?

Was there a historical Atlantis, and if so, when and where was it?

Why do the genealogies of Genesis and the Mesopotamian king lists have such seemingly long lived people?

How much of the books of Genesis and Exodus in the Bible derive from Mesopotamian lore? When and by whom were the various parts of these books of the Bible written? How much did Egyptian beliefs influence the early Hebrews?

Exactly what happened to the Jews in the diaspora after 70 CE and how did they come to be the Jewish peoples we know today?

What was the origin story of the gypsies?

Do the polytheistic deities of Greece, Scandinavia, Egypt, the ancient Mediterranean, the Americas, and India have any connections to real historic people? Is so, when and in what context?

What does the prehistoric and legendary history era chronology of human inhabitation of Southeast Asia and East Asia look like?

How far back can oral histories reliably describe the past? What are the most notable examples of this?

What is the origin story of the Japanese people? Where did the Jomon come from? How representative is the Ainu language of the language(s) of the Jomon people?

Are Korean and Japanese related linguistically? How? Is the larger Altaic linguistic family a legitimate linguistically related group of languages?

What undecipherable scripts of lost languages can we decipher?

What explains the relative strength and weaknesses of polygamy in different cultures at different times?

What was the lost agricultural civilization of the Amazon like?

What was the Mississippian culture like?

What were the dynamics of changing political/cultural region/linguistic control in the Americans in the pre-Columbian era that changed over time?

In Africa, was there an expansion within Africa parallel to the Out of Africa expansion? Why were modern humans suddenly so dynamic and behaviorally modern starting in the Upper Paleolithic era? What were the histories of the pre-Bantu language family expansions of languages in Africa? What is the story of the genetically distinct culture of click language speakers in Mozambique that left no pure blooded members of the "race" and no relict speakers of that language?

Is there any merit to the existence of a mostly lost Indo-Pacific language family made up of relict language isolates across Southern Asia?

) here is the decay rate, its inverse gives the time it takes for a cubic gigaparsec of space to experience vacuum decay. The three uncertainties are from experiments, the uncertainties of our current knowledge of the Higgs mass, top quark mass, and the strength of the strong force. . . . Vacuum decay might happen in as few as

years or as many as

years, and that’s the result of an actual, reasonable calculation!