A new paper on Basque genetics is out with both ancient and modern samples, honing in on the geographically localized heterogeneity of Basque genetics even within Basque country in Northern Spain and Southeastern France. Razib blogs it here without any real commentary except from his readers.

The paper shows that the Basques who speak the Basque language are indeed genetically distinct from their neighbors in Iberia and Southern France, with their immediately adjacent close neighbors, called "Peri-Basque" in the paper, being intermediate).

The Basque lack the genetic contributions of the Iron Age Romans and from the Moors in the Middle Ages is largely found in other Iberians. It also shows strongly small scale geographic variation in Basque genetics from subregion to subregion of Basque country.

It does not appear to show any real Basque distinctiveness attributable to earlier eras, although the paper slightly hedges its bets on that score. The lack of pre-Iron Age genetic differentiation is a finding that I am skeptical of given prior publications and the historical and linguistic context, although I don't rule it out, out of hand.

At least some Indo-European influences arrived in Iberia in the Bronze Age, not the Iron Age, and the Basque people obvious avoided cultural domination at that time, even though this paper's genetic analysis doesn't real reveal any genetic evidence in modern Basque people that this happened.

Certainly, the Romans are the source of all of the Romance languages spoken in Iberia today. But the pre-Roman linguistic character of Iberia is muddy, with Celtic languages present in or near parts of Iberia in pre-Roman times as well, for example, and the Bell Beaker phenomena originating there.

My ambivalence is, in part, because there is good reason based upon historical and linguistic evidence, to think that much more of Iberia was Vasconic in the pre-Roman era than it is today, with sister languages of the Basque language's going extinct in the face of Roman influence. It could be that influences distinct to Bronze Age Vasconic people are invisible because, apart from the Basque people, Iberian Vasconic people may have been thoroughly integrated into the Iberian general population in 85 or so generation that followed from Roman conquest until the modern samples were taken.

Another important conclusion reached, contrary to some of my conjectures in the past on the matter, is that there is no discernible Caucasian/Iranian farmer or Caucasian/Iranian hunter-gatherer ancestry found in the Basque population (or in the general Iberian population).

While it is well known that language shift can occur in a population whose population genetics are unchanged, the lack of a Caucasian/Iranian farmer genetic signal in Iberians still disfavors the possibility that Basque is a language that arrived in Iberian in the Copper Age/early Bronze Age from a Minoan/Hattic/Hurrian/Caucasian, pre-Indo-European Iranian, or Harappan source (all of which would be expected to have some of this genetic signal), or at least, that any migrants from these societies were few in number, making the likelihood that they brought about language shift in the Neolithic societies in which they arrived smaller. This component isn't entirely absent from Copper Age and Bronze Age Pontic Caspian steppe peoples (who did leave a discernible genetic impact on Iberians), but as Davidski notes in recent post at Eurogenes, it was a quite dilute and minor component.

Instead, this data point tends to favor (by process of elimination) the hypothesis that that Vasconic languages are derived from the first farmers of Iberia and its vicinity, which in turn would have been derived from the languages of the Western Anatolian first farmers who expanded into Europe in the European Neolithic Revolution, primarily in a Northern Linear Pottery Culture and cultures derived from it, and in a Mediterranean coastal Cardial Pottery culture and cultures derived from it, which would be the most plausible source for most Iberian farmers.

The paper is thinner on analysis and context that might be hoped given the depth of the literature on this particular matter, and does less to leverage its ancient DNA samples than it could, so I'll provide some context in this post to supplement it.

In the 6th millennium BC, Andalusia experiences the arrival of the first agriculturalists. Their origin is uncertain (though North Africa is a serious candidate) but they arrive with already developed crops (cereals and legumes). The presence of domestic animals instead is unlikely, as only pig and rabbit remains have been found and these could belong to wild animals. They also consumed large amounts of olives but it's uncertain too whether this tree was cultivated or merely harvested in its wild form. Their typical artifact is the La Almagra style pottery, quite variegated.

The Andalusian Neolithic also influenced other areas, notably Southern Portugal, where, soon after the arrival of agriculture, the first dolmen tombs begin to be built c. 4800 BC, being possibly the oldest of their kind anywhere.

C. 4700 BC Cardium pottery Neolithic culture (also known as Mediterranean Neolithic) arrives to Eastern Iberia. While some remains of this culture have been found as far west as Portugal, its distribution is basically Mediterranean (Catalonia, Valencian region, Ebro valley, Balearic islands).

The interior and the northern coastal areas remain largely marginal in this process of spread of agriculture. In most cases it would only arrive in a very late phase or even already in the Chalcolithic age, together with Megalithism.

The location of Perdigões, in Reguengos de Monsaraz, is thought to have been an important location. Twenty small ivory statues dating to 4,500 years BP have been discovered there since 2011. It has constructions dating back to about 5,500 years. It has a necropolis. Outside the location there is a cromlech. The Almendres Cromlech site, in Évora, has megaliths from the late 6th to the early 3rd millennium BC. The Anta Grande do Zambujeiro, also in Évora, is dated between the early 4th and the mid 3rd millennium BC. The Dolmen of Cunha Baixa, in Mangualde Municipality, is dated between 3000 and 2500 BC. The Cave of Salemas was used as a burial ground during the Neolithic.

The

Chalcolithic or Copper Age is the earliest phase of metallurgy. Copper, silver and gold started to be worked then, though these soft metals could hardly replace stone tools for most purposes. The Chalcolithic is also a period of increased social complexity and stratification and, in the case of Iberia, that of the rise of the first civilizations and of extensive exchange networks that would reach to the Baltic and Africa. The conventional date for the beginning of Chalcolithic in Iberia is c. 3000 BC. In the following centuries, especially in the south of the peninsula, metal goods, often decorative or ritual, become increasingly common. Additionally there is an increased evidence of exchanges with areas far away: amber from the Baltic and ivory and ostrich-egg products from Northern Africa.

The

Beaker culture was present in Iberia during the Chalcolithic.

Gordon Childe interpreted the presence of its characteristic artefact as the intrusion of "missionaries" expanding from Iberia along the Atlantic coast, spreading knowledge of Mediterranean copper metallurgy. Stephen Shennan interpreted their artefacts as belonging to a mobile cultural elite imposing itself over the indigenous substrate populations. Similarly, Sangmeister (1972) interpreted the "Beaker folk" (Glockenbecherleute) as small groups of highly mobile traders and artisans. Christian Strahm (1995) used the term "Bell Beaker phenomenon" (Glockenbecher-Phänomen) as a compromise in order to avoid the term "culture".

The Bell Beaker artefacts at least in their early phase are not distributed across a contiguous areal as is usual for archaeological cultures, but are found in insular concentrations scattered across Europe. Their presence is not associated with a characteristic type of architecture or of burial customs. However, the Bell Beaker culture does appear to coalesce into a coherent archaeological culture in its later phase.

More recent analyses of the "Beaker phenomenon", published since the 2000s, have persisted in describing the origin of the "Beaker phenomenon" as arising from a synthesis of elements, representing "an idea and style uniting different regions with different cultural traditions and background. "Archaeogenetics studies of the 2010s have been able to resolve the "migrationist vs. diffusionist" question to some extent. The study by Olalde et al. (2017) found only "limited genetic affinity" between individuals associated with the Beaker complex in Iberia and in Central Europe, suggesting that migration played a limited role in its early spread from Iberia. However, the same study found that the further dissemination of the mature Beaker complex was very strongly linked to migration. The spread and fluidity of the Beaker culture back and forth between the Rhine and its origin source in the peninsula may have introduced high levels of steppe-related ancestry, resulting in a near-complete transformation of the local gene pool within a few centuries, to the point of replacement of about 90% of the local Mesolithic-Neolithic patrilineal lineages.

The origin of the "Bell Beaker" artefact itself has been traced to the early 3rd millennium. The earliest examples of the "maritime" Bell Beaker design have been found at the Tagus estuary in Portugal, radiocarbon dated to c. the 28th century BC. The inspiration for the Maritime Bell Beaker is argued to have been the small and earlier Copoz beakers that have impressed decoration and which are found widely around the Tagus estuary in Portugal. Turek has recorded late Neolithic precursors in northern Africa, arguing the Maritime style emerged as a result of seaborne contacts between Iberia and Morocco in the first half of the third millennium BCE. In only a few centuries of their maritime spread, by 2600 BC. they had reached the rich lower Rhine estuary and further upstream into Bohemia and beyond the

Elbe where they merged with

Corded Ware culture, as also in the French coast of Provence and upstream the Rhone into the Alps and

Danube.

It is also the period of the great expansion of megalithism, with its associated collective burial practices. In the early Chalcolithic period this cultural phenomenon, maybe of religious undertones, expands along the Atlantic regions and also through the south of the peninsula (additionally it's also found in virtually all European Atlantic regions). In contrast, most of the interior and the Mediterranean regions remain refractary to this phenomenon.

Another phenomenon found in the early chalcolithic is the development of new types of funerary monuments: tholoi and artificial caves. These are only found in the more developed areas: southern Iberia, from the Tagus estuary to Almería, and SE France.

Eventually, c. 2600 BC, urban communities began to appear, again especially in the south. The most important ones are

Los Millares in SE Spain and Zambujal (belonging to

Vila Nova de São Pedro culture) in Portuguese

Estremadura, that can well be called civilizations, even if they lack of the literary component.

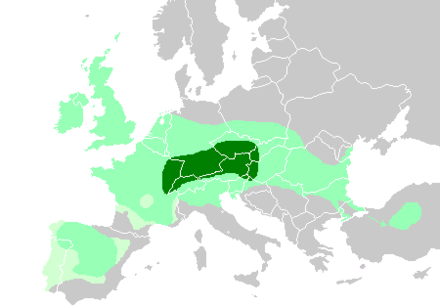

Extent of the Beaker culture

It is very unclear if any cultural influence originated in the Eastern Mediterranean (

Cyprus?) could have sparked these civilizations. On one side the tholos does have a precedent in that area (even if not used yet as tomb) but on the other there is no material evidence of any exchange between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, in contrast with the abundance of goods imported from Northern Europe and Africa.

Since c. 2150 BC, the Bell Beaker culture intrudes in Chalcolithic Iberia. After the early Corded style beaker, of quite clear Central European origin, the peninsula begins producing its own types of Bell Beaker pottery. Most important is the Maritime or International style that, associated especially with Megalithism, is for some centuries abundant in all the peninsula and southern France.

Since c. 1900 BC, the Bell Beaker phenomenon in Iberia shows a regionalization, with different styles being produced in the various regions: Palmela type in Portugal, Continental type in the plateau and Almerian type in Los Millares, among others.

Our knowledge of the cultures present in Iberia by the Bronze Age is patchy.

The picture is clarified somewhat, however, by the eve of Bronze Age collapse.Eventually, before Roman influence arrived in Iberia, however, most of the region was Celtic (and associated with this Indo-European linguistic family). This was an early Iron Age event:

The Iron Age in the Iberian peninsula has two focuses: the Hallstatt-related Iron Age Urnfields of the North-East and the Phoenician colonies of the South.

During the Iron Age, considered the protohistory of the territory, the Celts came, in several waves, starting possibly before 600 BC.

Since the late 8th century BC, the Urnfield culture of North-East Iberia began to develop Iron metallurgy and, eventually, elements of the Hallstatt culture. The earliest elements of this culture were found along the lower Ebro river, then gradually expanded upstream to La Rioja and in a hybrid local form to Alava. There was also expansion southwards into Castelló, with less marked influences reaching further south. Additionally, some offshoots have been detected along the Iberian Mountains, possibly a prelude to the formation of the Celtiberi.

During this period, the social differentiation became more visible with evidence of local chiefdoms and a horse-riding elite. It is possible that these transformations represent the arrival of a new wave of cultures from central Europe. From these outposts in the Upper Ebro and the Iberian mountains, Celtic culture expanded into the plateau and the Atlantic coast. Several groups can be described:

* The Bernorio-Miraveche group (northern Burgos and Palencia provinces), that would influence the peoples of the northern fringe.

* The north-west Castro culture, in today's Galicia and northern Portugal, a Celtic culture with peculiarities, due to the persistence of aspects of an earlier Atlantic Bronze Age culture.

* The Duero group, possibly the precursor of the Celtic Vaccei.

* The Cogotas II culture, likely precursor of the Celtic or Celtiberian Vettones (or a pre-Celtic culture with substantial Celtic influences), a markedly cattle-herder culture that gradually expanded southwards into what is today's Extremadura.

* The Lusitanian culture, the precursor of the Lusitani tribe, located in what is today's central Portugal and Extremadura in western Spain, is generally not considered Celtic since the Lusitanian language does not meet some the accepted definitions of a Celtic language. Its relationship with the surrounding Celtic culture is unclear. Some believe it was essentially a pre-Celtic Iberian culture with substantial Celtic influences, while others argue that it was an essentially Celtic culture with strong indigenous pre-Celtic influences. There have been arguments for classifying its language as either Italic, a form of archaic Celtic, or proto-Celtic.

All these Indo-European groups have some common elements, like combed pottery since the 6th century and uniform weaponry.

After c. 600 BC, the Urnfields of the North-East were replaced by the Iberian culture, in a process that wasn't completed until the 4th century BC.

Approximate extent of the Celts c. 400 BCE

However:

After c. 600 BC, the Urnfields of the North-East were replaced by the Iberian culture, in a process that wasn't completed until the 4th century BC. This physical separation from their continental relatives would mean that the Celts of the Iberian peninsula never received the cultural influences of La Tène culture, including Druidism.

The linguistic picture isn't really clearly documented until the eve of Roman conquest around 300 BCE, with the Iberian language probably sharing a linguistic family relationship with the Basque language.

The linguistic classification of the Tartessian language is controversial:

Tartessian is generally left unclassified for lack of data or proposed to be a language isolate for lack of connections to the Indo-European languages. Some Tartessian names have been interpreted as Indo-European, more specifically as Celtic. However, the language as a whole remains inexplicable from the Celtic or Indo-European point of view; the structure of Tartessian syllables appears to be incompatible with Celtic or even Indo-European phonetics and more compatible with Iberian or Basque; all Celtic elements are thought to be borrowings by some scholars.

Since 2009, John T. Koch has argued that Tartessian is a Celtic language and that the texts can be translated. Koch's thesis has been popularised by the BBC TV series The Celts: Blood, Iron and Sacrifice and the associated book by Alice Roberts.

However, his proposals have been regarded with scepticism by academic linguists and the script, which is "hardly suitable for the denotation of an Indo-European language[,] leaves ample room for interpretation". In 2015, Terrence Kaufman published a book that suggested that Tartessian was a Celtic language but written using a script devised initially for a Vasconic "Hipponic" language (numerous SW placenames in -i(p)po(n)) although there are no extant inscriptions in such a language using the Tartessian script.

The Tartessian culture appears to be the first Iberian culture in which there is major use of cattle:

The name Tartessian, when applied in archaeology and linguistics does not necessarily correlate with the semi-mythical city of Tartessos but only roughly with the area where it is typically assumed it should have been located.

The Tartessian culture of southern Iberia actually is the local culture as modified by the increasing influence of eastern Mediterranean elements, especially Phoenician. Its core area is Western Andalusia, but soon extends to Eastern Andalusia, Extremadura and the Lands of Murcia and Valencia, where a Tartessian complex, rooted in the local Bronze cultures, is in the last stages of the Bronze Age (ninth-eighth centuries BC) before Phoenician influences can be seen clearly.

The full Tartessian culture, beginning c.720 BC, also extends to southern Portugal, where is eventually replaced by Lusitanian culture. One of the most significant elements of this culture is the introduction of the potter's wheel, that, along with other related technical developments, causes a major improvement in the quality of the pottery produced. There are other major advances in craftsmanship, affecting jewelry, weaving and architecture. This latter aspects is especially important, as the traditional circular huts were then gradually replaced by well finished rectangular buildings. It also allowed for the construction of the tower-like burial monuments that are so typical of this culture.

Agriculture also seems to have experienced major advances with the introduction of steel tools and, presumably, of the yoke and animal traction for the plough. In this period it's noticeable the increase of cattle accompanied by some decrease of sheep and goat types.

Another noticeable element is the major increase in economical specialization and social stratification. This is very noticeable in burials, with some showing off great wealth (chariots, gold, ivory), while the vast majority are much more modest. There is much diversity in burial rituals in this period but the elites seem to converge in one single style: a chambered mound. Some of the most affluent burials are generally attributed to local monarchs.

Some of the key illustrations from the new Basque genetics paper follow:

The paper says this in its discussion section:

[O]ur analyses support the notion that the genetic uniqueness of Basques cannot be attributed to a different

origin relative to other Iberian populations but instead to a

reduced and irregular external gene flow since the Iron Age[.] The observed clines of postIron Age gene flow in the region suggest that the specific genetic profile of Basques might be explained by the lack of

recent gene flow received. Our analyses confirm that Basques

were influenced by the major migration waves in Europe until

the Iron Age, in a similar pattern as their surrounding populations.

At that time, Basques experienced a process of isolation,

characterized by an extremely low admixture with the posterior population movements that affected the Iberian Peninsula,

such as the Romanization or the Islamic rule, as observed in

the present genetic landscape.

This does not exclude plausible previous periods of isolation, as attested by the presence of short ROHs and small Ne

values that support signals of ancient inbreeding

in the region, even higher than in Sardinia, which is suggested

to be isolated after Neolithic times. Thus, the increase of the Ne

observed only in the external groups about 1,000 generations

ago might be potentially linked to the role of the Franco-Cantabrian region as glacial refugium during LGM periods and the

subsequent expansion.

Although our results support the genetic continuity from the Iron Age in most of the present day Basques, those located in the periphery of the Basque

core area show signals of contacts compatible with the Roman

Empire presence in the Iberian Peninsula.

These results are in agreement with archaeological and historical records. An important presence of the Roman Empire has

been reported in the whole Franco-Cantabrian region, but the

scholars suggest a much higher impact in the peripheral areas

of the southern side, specially Nafarroa and Araba. Otherwise, North African influence only fit the models where southern

and northwestern Iberians are included.

This confirms the reduced gene flow between the eastern

and northern areas of the Iberian Peninsula with the North

African incomers during the Islamic rule, as already reported

by using uniparental markers and more recently through

genome-wide data and haplotype-based methods.

The paper and its abstract are as follows:

Basques have historically lived along the Western Pyrenees, in the Franco-Cantabrian region, straddling the

current Spanish and French territories. Over the last decades, they have been the focus of intense research

due to their singular cultural and biological traits that, with high controversy, placed them as a heterogeneous, isolated, and unique population. Their non-Indo-European language, Euskara, is thought to be a major

factor shaping the genetic landscape of the Basques. Yet there is still a lively debate about their history and

assumed singularity due to the limitations of previous studies.

Here, we analyze genome-wide data of Basque

and surrounding groups that do not speak Euskara at a micro-geographical level. A total of �629,000

genome-wide variants were analyzed in 1,970 modern and ancient samples, including 190 new individuals

from 18 sampling locations in the Basque area. For the first time, local- and wide-scale analyses from

genome-wide data have been performed covering the whole Franco-Cantabrian region, combining allele

frequency and haplotype-based methods.

Our results show a clear differentiation of Basques from the surrounding populations, with the non-Euskara-speaking Franco-Cantabrians located in an intermediate position. Moreover, a sharp genetic heterogeneity within Basques is observed with significant correlation with

geography.

Finally, the detected Basque differentiation cannot be attributed to an external origin compared

to other Iberian and surrounding populations. Instead, we show that such differentiation results from genetic

continuity since the Iron Age, characterized by periods of isolation and lack of recent gene flow that might

have been reinforced by the language barrier.

Frederic Bauduer, et al., "Genetic origins, singularity, and heterogeneity of Basques" 31 Current Biology 1-11 (May 24 2021) (online ahead of publication). doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.010