In a nutshell

A new bioRxiv pre-print examining the ancient DNA of a man and a woman from 200 BCE shows that there is strong continuity between the original Austronesian settlers of the Mariana Islands ca. 1500 BCE (maternally at least 92%) and possibly as early as 2300 BCE, the best known of which is Guam, and the present Chamorro language speaking residents of the island chain.

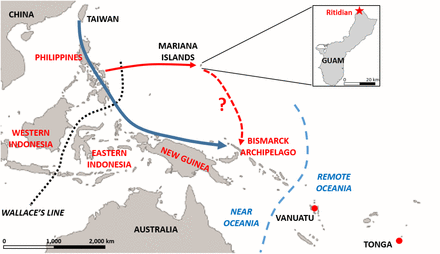

Genetic, linguistic and archaeological evidence all support the conclusion that these islands were settled by a genetically very similar, but culturally distinct sister people to the Lapita people (who were the Austronesian founding population of Oceania), and had more in common culturally and linguistically with the Austronesians who colonized the Philippines and the Western part of island Southeast Asia.

Where are the Mariana Islands?

Guam is the southernmost and most populous of a chain of islands known as the Mariana Islands which are east of the Philippines and Taiwan, in a line that if further extended would run from Japan in the north to Papua New Guinea to the south. Today, this island chain is organized into two self-governing U.S. territories, Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, with a combined population of about a quarter of a million people.

Image from here.

The Story So Far . . .

The Austronesian people, whose origins have been traced genetically and linguistically to a subset of the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, because they were the first really advanced long range mariners in human history, expanded to an immense range from Hawaii and Easter Island in the east, to New Zealand in the south, to Madagascar of the coast of Africa in the west. They were the primary post-Negrito human settlers of the Philippines and island Southeast Asia.

The Austronesian expansion from Taiwan began about 3000 BCE ± a few hundred years, reached to Philippines around 2000 BCE, to the rest of island Southeast Asia and coastal mainland Southeast Asia not long afterwards, and reached Fiji about 1500 BCE.

Then this first wave of Austronesian expansion paused for a thousand years hundred years. The expansion to more remote parts of Polynesia and Madagascar was renewed starting sometime around 300-500 CE eventually resulting in the Austronesian people settling Madagascar (together with East Africans) and the Society Islands, and reached its fullest extent around 1100 CE with the arrival of the Maori people in New Zealand and making limited contact involving exchanges of chickens, women, and yams with at least a couple of places in South America. The archaeological evidence suggests that the Polynesians appear to have made renewed contact to the people of the Mariana Islands at the very end of this second expansion, around 1000 CE.

The map above, with my annotations correcting the route to Madagascar based upon a February 2019 paper, is from a prior post at this blog.

People speaking languages descended from the earliest Austronesians in Tawain, with substantial genetic ancestry from them were the first human inhabitants of basically all of Oceania aside from some islands that could be reached with line of sight navigation from island to island starting with Papua New Guinea which were first settled by modern humans at the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic era about 50,000 years ago.

Linguistically, the Austronesian languages which were spread by the Austronesian expansions have five main families with geographic ranges shown below:

Before the Lapita people had expanded very far, however, around 300-500 CE, a male dominated group of people with Papuan ancestry conquered them in Tonga and Vanuatu and contributed significantly to these populations genetically, while ultimately assimilating culturally into speaking an Austronesian language presumably derived from the language of the Lapita people with possibly Papuan or language learner influences, and other aspects of Lapita culture.

Almost all of the rest of Oceania, in turn, was settled by these people with mixed Austronesian Lapita and Papuan ancestry with a predominantly Austronesian culture. Polynesians and other Oceanians descended from Polynesians have about 25% Papuan (a.k.a. Melanesian) autosomal DNA, 6% Papuan mtDNA (which is passed from mother to child), and 65% Melanesian in Y-DNA.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the culture of the Mariana Islands was more or less static from 2300 BCE to 1000 CE. As the body text of the preprint explains:

These linguistic and cultural differences have led most scholars to conclude that the settlement of western Micronesia and Polynesia had little to do with one another. To be sure, indications have been noted of morphological, cranial, and genetic affinities between Micronesians and Polynesians, and stylistic links between the pottery of the Philippines, the Marianas, and the Lapita region have also been illustrated.

Nonetheless, the standard narrative for Polynesian origins is that they reflect a movement of Austronesian-speaking people from Taiwan beginning 4-5 kya that island-hopped through the Philippines and southeastward through Indonesia, reaching the Bismarck Archipelago around 3.5 – 3.3 kya. From there they spread into Remote Oceania, with subsequent additional migrations from Near Oceania around 2.5 kya that brought more Papuan-related ancestry into Remote Oceania. This narrative is supported by a large body of archaeological, linguistic, and genetic data, and western Micronesia typically does not figure in this orthodox story.Compared to Polynesians, the origins of the Mariana islanders are more uncertain.

Most mtDNA sequences of modern Chamorros belong to haplogroup E, which occurs across Island Southeast Asia and is thought to be associated with the initial peopling of the Marianas, while the less-frequent haplogroup B4 sequences, which are found in high frequency in Polynesians, are attributed to later contact.

Studies of a limited number of autosomal short-tandem repeat loci similarly indicate differences in the affinities of western Micronesians (Palau and the Marianas) vs. eastern Micronesians, with the former showing ties to Southeast Asia and the latter to Polynesia.

The linguistic evidence for Chamorro would suggest an origin from western Indonesia or the Philippines, and the oldest decorated pottery and other artifacts of the Marianas, dating to around 3.5 kya, have been matched with counterparts in the Philippines at around the same time or even earlier. However, alternative views have been proposed and debated, and it is not clear to what extent the genetic and linguistic relationships of the contemporary Chamorro reflect initial settlement vs. later contact. Moreover, computer simulations of sea voyaging found no instances of successful voyaging from the Philippines or western Indonesia across to the Marianas; instead these simulations indicated New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago as the most likely starting points.

Genomic evidence can shed light on this debate over the origin of the Chamorro, as well as on their relationships with Polynesians. Two main genetic ancestries are present in New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago: the aforementioned Austronesian (Malayo- Polynesian), which arrived with the spread of Austronesian speakers from Taiwan, and “Papuan,” which is a general term for the non-Austronesian ancestry that was present in New Guinea and Island Melanesia prior to the arrival of the Austronesians; it should be kept in mind that “Papuan” ancestry is quite heterogeneous in composition across the region.

Papuan-related ancestry probably traces back to the original human populations of the region, at least 49 kya, and is readily distinguished from Austronesian ancestry. Papuan-related ancestry is present not only in New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago, but also at substantial frequencies in eastern Indonesia, defined here as all Indonesian islands to the east of Wallace’s line. However, Papuan-related ancestry is practically absent west of Wallace’s Line, so if the first settlers of the Marianas started from the Philippines or west of Wallace’s Line, then they should have had little if any Papuan-related ancestry. Conversely, if they started from eastern Indonesia, New Guinea, or the Bismarck Archipelago, then they should have brought appreciable amounts of Papuan-related ancestry.In principle, to address this issue, the ancestry of the modern inhabitants of the Marianas could be analyzed for Papuan-related ancestry. However, a common finding of ancient DNA studies is that the ancestry of people in a region today may not reflect the ancestry of people living in that region thousands of years ago.

In particular for the Marianas, the archaeological evidence indicates substantial cultural change around ~1 kya, coinciding with the construction of stone-pillar houses in formal village arrangements (latte) at a time when nearly all of the Pacific Islands were populated and connected by long-distance sea voyaging. The presence of mtDNA haplogroup B4 sequences in modern Chamorro has been attributed to contact during the latte period.In addition, population contacts and movements became more complicated during the European colonial period, starting with the arrival of Magellan in 1521 in the Marianas and continuing with the Manila-Acapulco galleons (and slave trade) from 1565-1815; Guam was a regular stopover on these voyages. European colonialism also involved multiple relocations and reductions in population size across the archipelago. These events undoubtedly had an impact on the genetic ancestry of the modern Chamorros, making it more difficult to assess their origins and potential relationships with Polynesians. It would therefore be preferable to address these issues with ancient DNA from the Marianas.At the Ritidian Site in northern Guam, two skeletons clearly pre-dating the latte period were found outside a ritual cave site. These individuals, RBC1 and RBC2, were buried side-by-side in extended positions, with heads and torsos removed. Direct radiocarbon dating of a bone from RBC2 produced a result of 2180 +/- 30 years calibrated years bp, which is thus some 1000 years after the initial settlement of Guam, but also some 1000 years before the latte period.

The geographic distribution and estimated time depth of mtDNA B4a1a (which includes the "Polynesian motif") suggests that it may be Papuan in origin.

The New Ancient Mariana Islands DNA Findings

Haplogroup E2a is the most common haplogroup in the modern Chamorro population of Guam, with a frequency of 65%. Elsewhere it is reported to occur sporadically in populations from the Philippines and Indonesia, and in a single individual from the Solomon Islands; otherwise, it is absent from Oceania and has not been reported from Mainland Southeast Asia.

The finding of this haplogroup in the ancient Guam skeletons thus suggests links to the Philippines and Indonesia, rather than New Guinea or the Bismarck Archipelago.

Of additional importance, the high frequency of this haplogroup in modern Chamorros suggests a degree of genetic continuity with the population represented by the ancient skeletons, persisting through the interceding cross-population contacts since the latte period after ~ 1 kya and later European colonial events.

Haplogroup E is found throughout Maritime Southeast Asia. It is nearly absent from mainland East Asia, where its sister group M9a (also found in Japan) is common. In particular, it is found among speakers of Austronesian languages, and it is rare even in Southeast Asia among members of other language families. It has been detected in populations of Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia (including Sabah of Borneo, but not the Orang Asli of peninsular Malaysia), coastal Papua New Guinea, and especially in the Chamorros of the Mariana Islands.Of the four principal subclades, E1b and E2a are found mainly in Maritime Southeast Asia, while only E1a and E2b are also found in Taiwan. E2b has low diversity within Taiwan, suggesting that it arrived there about 5,000 years ago. The most common E subclade, E1a1a, has highest diversity in Taiwan, followed by the Philippines and Sulawesi. Moreover, other branches of E1a1 are largely confined to Taiwan.

The man has Y DNA haplogroup O2a2-P201 found in mainland Southeast Asia, the islands of Southeast Asia and Oceania. The preprint explains that:

Based on the ratio of the average coverage of X chromosome vs. X chromosome + autosomal reads in the shotgun sequencing data, RBC1 is male and RBC2 is female. The Y chromosome of RBC1 is assigned to haplogroup O2a2 (formerly haplogroup O3a3), based on having the derived allele for the diagnostic marker P201; genotypes at all other informative Y-chromosome SNPs for which there are data from RBC1 are consistent with this haplogroup. Haplogroup O2a2-P201 is widespread across Mainland and Island Southeast Asia and Oceania, and has been associated with the Austronesian expansion.

This clade includes the major subclades O2a2b1-M134 (subclade of O-P164) and O2a2a1a2-M7, which exhibit expansive distributions centered on China, as well as an assortment of Y-chromosomes that have not yet been assigned to any subclade.O2a2-P201(xO2a2a1a2-M7, O2a2b1-M134) Y-DNA has been detected with high frequency in many samples of Austronesian-speaking populations, in particular some samples of Batak Toba from Sumatra (21/38 = 55.3%), Tongans (5/12 = 41.7%), and Filipinos (12/48 = 25.0%). (Karafet 2010)

Outside of Austronesia, O2a2-P201(xO2a2a1a2-M7, O2a2b1-M134) Y-DNA has been observed in samples of Tujia (7/49 = 14.3%), Han Chinese (14/165 = 8.5%), Japanese (11/263 = 4.2%), Miao (1/58 = 1.7%), and Vietnam (1/70 = 1.4%) (Karafet 2010 and Nonaka 2007).

About 30.6% of Filipinos, 25% of Polynesians and 12.6% of aboriginal Taiwanese people have a Y-DNA haplogroup in the O-M122 clade which is the parent Y-DNA clade of O-P201. Y-DNA O-M122 is the dominant Y-DNA clade of Polynesians who are not among the roughly 65% with Y-DNA haplogroups of Papuan origin.

Within the Han Chinese, O-P201 is found predominantly in Southern China as opposed to Eastern or Northern China.

This Y-DNA haplogroup is not, however, found in Papuans, unlike the Y-DNA haplogroups of about 65% of Polynesian men.

The autosomal DNA results

The two ancient Mariana Islands samples have no traces Papuan, aboriginal Australian, distinctively Malaysian, or distinctively East Asian ancestry. One sample shows a small proportion of West Eurasian ancestry due to contamination in the sample. Other than this contamination, the samples have ancestry exclusively associated with the aboriginal Taiwanese and Austronesian people in an ancestry component analysis.

A principle component analysis confirms a lack of any Papuan (a.k.a. Melanesian) or West Eurasian ancestry.

As Bernard explains at his blog (with translation from the French via Google with minor editorial changes by me):

The f3 and f4 statistics show that the ancient Guams have the most genetic affinity with an ancient Lapita from Vanuatu, an ancient Lapita from the Tonga Islands, an 1850 year old sample from the Philippines, and the present populations of Taiwan and the Philippines. . . .

However, the ancient Lapita people show more genetic affinity with the Polynesian populations than the ancient Guam. So even if the ancient Guams are close to the ancient Lapita, the latter constitute a better genetic source for the Polynesians. . . .

It is possible that the ancestors of the early Lapita passed the Marianas. It is also possible that the ancestors of the Lapita and those of the Guam migrated separately from Taiwan and the Philippines: the former to the Bismarck Archipelago and the latter to the Marianas.

My Conjectures

For what it is worth, I am inclined to think that it is more likely that the Marianas and the Bismarck Islands were settled in separate migrations from the Philippines (and not directly from Taiwan), separated by about a thousand years, and that the settlement of the Marianas, unlike the settlement of the Bismarck Islands, which may have involved some ongoing interaction with the Philippines, was a one time, one way expedition. The descendants of the original settlers of the Mariana Islands were probably completely isolated from the rest of the world from about 2300 BCE to about 200 CE or later, in order words, for about 2500 years, and may not have had any really significant interaction with the outside world until about 1000 CE, with no truly demographically or linguistically disruptive contact until the 1500s CE.

Most likely this was a case of a substantial group of people who had set out on a much less ambitious trip getting lost or by carried off by a storm, that was not intended as an effort to colonize the islands where they ended up (which they may not have even known existed) which explains why well developed pottery like the Lapita pottery style, and the package of domesticated animal found in other Austronesian settlements, was absent in the Mariana islands.

Another possibility is that the journey of the founding population of the Mariana islands, while extraordinary and probably not repeatable, was made not directly from the Philippines, but from the Bismarck Islands, as computerized navigational simulations suggest would be more viable.

The authors of the paper suggest that if this route was taken that one would expect some Papuan ancestry in the Chamorro people that is entirely absent. But, if the people of Papua New Guinea were only able to reach some of the Bismarck Islands on the boats of the Lapita people, and the proto-Chamorro people didn't make contact with already inhabited Bismarck Islands or did so only briefly without staying long enough for any child bearing couples to result (or simply left any such couples left behind in the Bismarck Islands), then this more navigable route is not ruled out. The study does address this possibility, but largely dismisses it (perhaps too blithely) stating:

A Philippine source for the foundational population of Guam is consistent with the findings of modern DNA sampling, the linguistic evidence, and the archaeological signature at the time of first Marianas settlement about 3.5 kya. However, computer simulations of sea voyaging instead have indicated New Guinea or the Bismarck Archipelago as probable origin points of voyages reaching the Marianas.One potential scenario to reconcile these two lines of evidence is that people traveled from the Philippines to New Guinea or the Bismarcks, without mixing with any populations along the way, and then voyaged from New Guinea/the Bismarcks to Guam, again without first mixing with any resident populations.However, the TreeMix and AdmixtureBayes results do not support this scenario, nor does the linguistic and archaeological evidence. In particular, the earliest pottery in the Marianas, dating to around 3.5 kya, likely predates the oldest Lapita sites to the east of New Guinea, dated to not more than 3.3 kya. Yet the pottery, fine shell ornaments, and other cultural objects in the Marianas dating to 3.5 kya are quite distinct from the Lapita tradition, and instead can be linked to material markers in the Philippines that date to 3.8-3.5 kya, thus supporting movement from the Philippines to the Marianas.Moreover, the computer simulations of sea voyaging do not adequately consider the ability of ancient voyagers to travel against strong ocean currents and prevailing winds; in particular, the single outrigger canoes of the Chamorros - the ‘flying proas’ - impressed early visitors with their greater speed and maneuverability, compared to Spanish ships. There is even at least one historically documented event of a Chinese trader drifting in a “sampan” from Manila to Guam during the 1600s. Ancient DNA from early Lapita skeletons in the Bismarcks would provide a further test of the hypothesis that people moved from the Bismarcks to Guam.

The lack of Papuan genetic admixture does little to disfavor of Bismarck route because the Lapita people didn't show any sign of Papuan admixture until about 300-500 CE themselves. Papuan admixture is absent from the ancient Lapita samples from Vanuatu and Tonga dating to after the time period when the Mariana Islands were settled as well.

Since all of the relevant cultures were illiterate until the last few hundred years or so, we also can't rule out the possibility that the linguistic distinctiveness of the Oceanic languages doesn't have its origins in contact with Papuan languages at some time after the Mariana Islands were settled.

Indeed, all of the language families of the Austronesian languages except in Taiwan and the Western Mayalo-Polynesian family could be attributable to language contract with greater Papuan languages.

Why would they have not settled in the Bismarck Islands and left an archaeological trace before moving on?

Perhaps my hypothesis that the Papuan ancestry people did not reside in the Bismarck Islands already was wrong, and instead, the settlers of the Mariana Islands decided that they didn't want to have to compete with the existing residents of those islands and instead moved on as soon as they could. And, if the settlers of the Mariana Islands preceded the Lapita people by two hundred years, and lacked contact with Papuan peoples that may have influenced the Lapita people artistically, it is hardly surprising that their pottery designs did not differ much from those of their penultimate source in the Philippines, while the Lapita people's designs did.

I am also skeptical of claims that the original settlers of the Mariana Islands were such superior maritime travelers that assumptions of the computer models could be disregarded, when the Mariana Island residents showed no signs of making subsequent long distant travels after arriving, didn't return to the place of origin to secure and bring back dogs, pigs or chickens, and no other trips of this magnitude were made to any other destinations from the Philippines in that era.

All of the historical anecdotes that the authors use to support the excellent maritime capabilities of the Chamorro people date to after the latte period when the Chamorro people had been in contact with Polynesians and admixed with them to a minor extent, when they could have learned the maritime skills attested to in the 16th century CE.

In any case, regardless of the route by which they arrived, it is safe to conclude the extant Chamorro people and their language (in the most archaic attested forms known) are probably the closer genetically and linguistically to the original Austronesian explorers and colonizers to any other people or language, because they, unlike the Austronesian ancestors who stayed in Taiwan or in the Philippines had much more contact with other languages that could lead to linguistic borrowing, language learner effects, and other sources of linguistic change.

The small size of the founding population of the Chamorro people and their reduced economic circumstances and isolation, especially early on, however, may have led to some significant loss of vocabulary (even core vocabulary) and linguistic complexity.

The most analogous case in Europe would be that of Icelandic, which is the Germanic language closest to the Germanic protolanguage also known as Old Norse, because it was almost completely isolated from most other language contact for perhaps seven or eight hundred years.

The pre-print's abstract

The abstract of the new pre-print is as follows (emphasis added):

Humans reached the Mariana Islands in the western Pacific by ~3500 years ago, contemporaneous with or even earlier than the initial peopling of Polynesia. They crossed more than 2000 km of open ocean to get there, whereas voyages of similar length did not occur anywhere else until more than 2000 years later. Yet, the settlement of Polynesia has received far more attention than the settlement of the Marianas. There is uncertainty over both the origin of the first colonizers of the Marianas (with different lines of evidence suggesting variously the Philippines, Indonesia, New Guinea, or the Bismarck Archipelago) as well as what, if any, relationship they might have had with the first colonizers of Polynesia. To address these questions, we obtained ancient DNA data from two skeletons from the Ritidian Beach Cave site in northern Guam, dating to ~2200 years ago.

Analyses of complete mtDNA genome sequences and genome-wide SNP data strongly support ancestry from the Philippines, in agreement with some interpretations of the linguistic and archaeological evidence, but in contradiction to results based on computer simulations of sea voyaging.

We also find a close link between the ancient Guam skeletons and early Lapita individuals from Vanuatu and Tonga, suggesting that the Marianas and Polynesia were colonized from the same source population, and raising the possibility that the Marianas played a role in the eventual settlement of Polynesia.

The body text of the paper notes that:

The earliest archaeological sites date to around 3.5 thousand years ago (kya), and paleoenvironmental evidence suggests even older occupation, starting around 4.3 kya. Thus, the first human presence in the Marianas was at least contemporaneous with, and possibly even earlier than, the earliest Lapita sites in Island Melanesia and western Polynesia that date to after 3.3 kya and are associated with the ancestors of Polynesians.

However, reaching the Marianas necessitated crossing more than 2000 km of open ocean, whereas voyages of similar length were not accomplished by Polynesian ancestors until they ventured into eastern Polynesia within the past 1000 years.

Footnote

Chamorro society was divided into two main castes, and continued to be so for well over a century after the Spanish first arrived. According to historical records provided by Europeans such as Father Charles Le Gobien, there appeared to be racial differences between the subservient Manachang caste, and the higher Chamor[r]i, the Manachang being described as shorter, darker-skinned, and physically less hardy than the Chamori. The Chamori caste was further subdivided into the upper-middle class Achoti/Acha'ot and the highest, the ruling Matua/Matao class. Achoti could gain status as Matua, and Matua could be reduced to Achoti, but Manachang were born and died as such and had no recourse to improve their station. Members of the Manachang and the Chamori were not permitted to intermingle. All three classes performed physical labor, but had specifically different duties. Le Gobien theorized that Chamorro society comprised the geographical convergence of peoples of different ethnic origins. This idea may be supportable by the evidence of linguistic characteristics of the Chamorro language and social customs.

An ancient DNA sample of just two individuals can't shed any real light on a hypothesis like this one (that caste practices among these peoples corresponded to differences in ancestry).

But the mtDNA mix referenced in the preprint from prior works and the article cited in this post, do not support any meaningful substructure that one would expect if there was an ancestry based caste system, and there is likewise no indication in the genetic literature I've seen that there is an obvious substructure or discontinuity within this population (or that there was once one that collapsed only in the last two hundred years due to admixture which would still leave great diversity in autosomal DNA and uniparental haplotypes within the population that are not seen).

Instead, there is every indication of a homogeneous population with a single very remote origin, with material admixture only on the order of 8% or so since 1000 CE.

If so, any physically apparent differences would have to be a result, not of genetics, but of differences in nutrition and the nature of their physical activity.

Second Footnote

In the course of writing this post I came across another open access paper from 2014 on Austronesian origins based upon ancient DNA that deserves mention. The abstract of the paper is as follows:

A Taiwan origin for the expansion of the Austronesian languages and their speakers is well supported by linguistic and archaeological evidence. However, human genetic evidence is more controversial. Until now, there had been no ancient skeletal evidence of a potential Austronesian-speaking ancestor prior to the Taiwan Neolithic ∼6,000 years ago, and genetic studies have largely ignored the role of genetic diversity within Taiwan as well as the origins of Formosans.

We address these issues via analysis of a complete mitochondrial DNA genome sequence of an ∼8,000-year-old skeleton from Liang Island (located between China and Taiwan) and 550 mtDNA genome sequences from 8 aboriginal (highland) Formosan and 4 other Taiwanese groups.

We show that the Liangdao Man mtDNA sequence is closest to Formosans, provides a link to southern China, and has the most ancestral haplogroup E sequence found among extant Austronesian speakers. Bayesian phylogenetic analysis allows us to reconstruct a history of early Austronesians arriving in Taiwan in the north ∼6,000 years ago, spreading rapidly to the south, and leaving Taiwan ∼4,000 years ago to spread throughout Island Southeast Asia, Madagascar, and Oceania.